Topps 150 Years of Baseball #9—Rookie Campaigns

I have to admit, I’m hesitant to move to 1b so soon in this series. I have the strong impulse, having nubbed one towards the middle of the diamond, to take off running the bases backwards here and head towards 3b. Not because I so want to tell the stories of certain 3b (although maybe?), but because I wanted to hold off a little longer on getting to my personal childhood hero and a true legend of the game. Because, yes, it may surprise you to find out — Willie McCovey turned out to be a pretty good baseball prospect!

Nonetheless, at my age you have to know who you are and one thing I know about myself is that I follow the lines that are drawn — and so here we arrive at 1b in our journey through the greatest minor league seasons in Giants’ history. Not surprisingly we’ll find big, big power here — some of which proved to be real and true and lasting, and some of it was just…

Why Didn’t that Guy Make It?

Starting 1b

Skip James, 1972 Fresno Giants (California League - A), 22 years old

.292/.409/.564, 138 Runs, 123 RBI, 21 2b, 32 HR, 87 BB, 81 K

1976 Kramer Phoenix Giants collection

While researching this project, the collection of potential 1b candidates was one of the larger pools that had to be whittled down. And, by and large, it wasn’t too hard to draw a connecting line between these big powerful, guys who seemed like they were going to be turning into the next big, powerful thing and then didn’t. Most of our candidates were some combination of: 1) old for their level; 2) repeating their level; 3) playing in offense-friendly environments; or 4) all of the above.

So you’ve got the current Sacramento hitting coach Damon “Tiny” Minor, bashing away at the PCL when he was 26 years old, playing in the very comfy climes of Beiden Field in Fresno (where Pedro Feliz led the team with 33 HRs and Giuseppe Chiramonte had 60 XBH). Or 24-year-old J.R. Phillips posting a 1.000+ OPS in Phoenix in his second season in the league. Or one of my personal favorites — 22-year-old Loyola Marymount grad Jesse Ibarra. In his first full season of pro ball the switch-hitter set the Midwest League on fire, crushing 34 HRs and 30 doubles in a monster 1.070 OPS destruction of A ball pitching. Man did 30-something Roger have big plans for Jesse’s future stardom (I have stories to tell of misplaced prospect optimism, let me assure you)!

But the “man among boys” seasons that really jumps off the page for me is Skip James’ astonishing Fresno campaign. To say that the 1972 season was an aberration in the career of the two-sport star from the University of Kansas, would be to chart new levels in the art of understatement. In that first full pro season, the college kid would crush 32 home runs to lead the California League — and not by a little! Future Giant Hector “Heity” Cruz (then a Cardinals farmhand) was second in the league with just 22 HRs (albeit in about 2/3 of a season). And it’s not like Fresno was a homer haven itself — only four members of the team even had double digits in home runs that year. It was just James, swinging and bashing and swinging and bashing and swinging and bashing some more from one end of the season to the other. Thirty-two home runs! On June 13, James crushed two homers to give him 16 on the year to go along with 56 RBIs. He was roughly half way through the year and by seasons end he would basically double both totals. His 20th on July 5 was a 10th inning walkoff. Another two-homer performance in late August boosted him near the 30 mark. Like a metronome, he just kept on ticking. That winter he headed to the Mexican League for more action and he kept on hitting home runs.

And then spring 1973 came…and it stopped. Over the next four seasons combined — all in Phoenix, all in the PCL — James would hit a total of 26 HRs! As if his power just dried up and blew away on the desert winds. Pushed straight from A ball to AAA in 1973, James would hit a mere 4 home runs in 129 games. There would be adjustments and swing changes — ironically, in June, James would credit hitting coach Hank Sauer for an adjustment that made his swing longer, which isn’t normally considered a great thing. But nothing worked. The next spring, after getting off to a .300 start through the first month of the year, he’d say: “I think I let the league scare me a little last year.” But his supposed greater comfort level didn’t bring back the power. He hit just 9 home runs that year, followed by 7 the next.

In all, the 32 round-trippers he hit in 1972 accounted for more than a third of his entire 9 season career. Only one other time would he manage to hit as many 10 home runs again: five years later in his fifth AAA campaign he’d get all the way to 14 longballs. That’s in American pro ball — James did play one year in Japan at the tail-end of his career and there his power swing re-emerged. His 21 home runs in 1980 was not only the second best season of his career, it was tied for 11th best in the NPB.

In the end, James was likely just a college veteran taking advantage of a low level and good hitting environments. But it is worth noting that the strong control of the strike zone he displayed in the Cal League was something that never left him, even in all those years he struggled in AAA. He had nearly 100 more walks than strikeouts in his minor league career, and even managed 6 walks in his brief MLB career — the same number as he had hits and RBIs.

Oh yes, James did have a major league career. That fifth year in the PCL, when he hit 14 home runs, he also had a .308 average and .919 OPS which earned him, at long last, his entrée to the Show. And on a crisp September night in 1977, in just the second, and final, start of his career, his two-run single capped a come-from-behind victory over the Dodgers. Not too shabby. Two nights later he’d knock in the winning run as a 9th inning pinch hitter in San Diego. And… that was it for the offensive highlights of James’ major league career. But he tagged along for much of the wild ride of 1978, serving as Willie McCovey’s defensive replacement through the first half of the year. Over 41 games, James got 26 PA and stroked two hits. And the big league career of the 5th rounder out of Kansas was done.

On the Bench

Gary Krupsky, 1958 Artesia Giants (Sophomore League - D), 19 years old

.311/.406/.578, 116 Runs, 142 H in 120 Games, 26 2b, 23 HR, 94 RBI

As much as I wanted to stick Jesse Ibarra’s monster year in here, the little remembered Gary Krupsky earns the nod as the only teenager among my candidates. Krupsky was a little free-swinging, piling up 107 strikeouts. Still the left-handed swinging teenager led the long-forgotten Sophomore League in total bases with 259, bashing 60 XBH. And if that’s not enough, he served as a relief pitcher for the team as well, though his 24 BB in 35 IP was maybe a warning sign that that part of his game wasn’t going anywhere. It’s an old story. Krupsky’s numbers came down as he went up and by 1961 he was finished. But, like so many others, his love for the game didn’t die with his pro career. He went home and joined the NYPD (it’s unknown whether Officer Krupsky interacted with any Jets or Sharks) and started the first NYPD Blues baseball team. From there it was on to coaching at Queens College and ultimately many years of youth baseball. He coached the National 17-U Championship team in 2008, the pinnacle of his career in the game.

Future Big Leaguer

Starting 1b

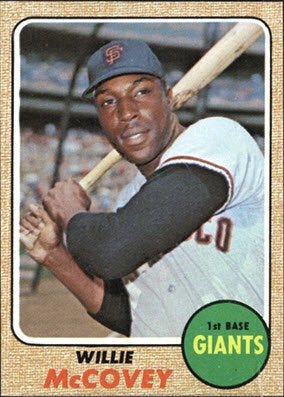

Willie McCovey, 1959 Phoenix Giants (Pacific Coast League, AAA), 21 years old

.372/.459/.759, 26 2b, 11 3b, 29 HRs, 95 RBI, 51 BB, 48 K in 95 games

There was never any doubt that young Willie McCovey could hit. As a 17 year old, he clubbed 19 HRs and had a league leading 113 RBI (in just 107 games) for the Sandersville Giants of the Georgia State League. His mostly older teammates that year hit a combined 53 HRs (with only one other player reaching double digits). The following season in the Carolina League the 18 year old was a force to be reckoned with, crushing 29 more homers and a league leading 38 doubles, slugging almost .600. He once knocked in 7 runs in a game with a homer, triple, and double. Along with teammate Leon Wagner (51 HRs!!!) McCovey led the Danville team to the playoffs where he had two different two-homer games. Even as a teenager, his swing was impactful enough to make him an instant starter for the highly competitive Escondido club in Dominican Winter ball.

One imagines that even then, as a kid barely old enough to be graduating from high school (which Willie never did — he had dropped out to work and help the family’s finances), one can imagine that scenes played out identically to that later one that Jim Bouton memorably described in Ball Four:

“A group of terrorized pitchers stood around the batting cage watching Willie McCovey belt some tremendous line drives over the right-field fence. Every time a ball bounced into the seats we’d make little whimpering animal sounds. ‘Hey, Willie,’ I said. ‘Can you do that whenever you want to?’ He didn’t crack a smile. ‘Just about,’ he said, and he hit another one. More animal sounds.”

But a badly sprained ankle (the first of a litany of health woes) curtailed his AA season at 19. In 1958, the ankle and the start of sore knees troubled him throughout his age 20 season in Phoenix — though he put up an .894 OPS for the league champions nonetheless. He was already wearing heavy knee braces by the following spring training, where the big league staff looked him over and quickly sent him back to minor league camp. Why would the Giants need another 1b anyway? They had two terrific ones, with Orlando Cepeda coming off his brilliant Rookie of the Year campaign and Bill White who had picked right back up hitting after missing two years in the military.

Why indeed? Over the next three and a half months, McCovey would more than amply demonstrate why the Giants needed another 1b. How does one sum up the terror that 21-year-old Willie McCovey inflicted on PCL pitchers over the course of that spring and summer of 1959? You can try to do it statistically, of course. Willie produced a statistical oddity that is always one of my Holy Grails for identifying elite prospects — he had more XBH (66) than strikeouts (48). He had more walks too. Or how about this: his .759 Slugging Percentage was exactly .200 points higher than the next highest in the league — Frank Howard’s .559. Howard, who is possibly the most underrated great slugger in big league history (thanks to two really unforgiving home ballparks) was himself on his way to a big league debut that summer, but he couldn’t hold a candle to Willie. Howard’s .921 OPS (third in the league) was almost exactly .300 points lower than McCovey’s incredible 1.219.

But no, all of that wasn’t really it. Yes, he led his league in batting, on base, and slugging, but that wasn’t it either. What was really it was the experience of McCovey, his slashing swing that you could hear ripping the air apart. Vicious. It was always referred to as vicious. Though he may have been the most gentle man alive, Willie McCovey had a vicious swing and he used it to unleash vicious shots on wary pitchers and fielders. If you read Joe Posnanski’s great piece on McCovey from his astonishing Baseball 100 series, you read quote after quote about the fear that McCovey inspired in his opponents. My favorite of them was from Sparky Anderson (who intentionally walked McCovey in nearly every situation):

Let me just tell you, I shake just when I walk past Willie McCovey.

Finally at the end of July, the Giants had taken all they were going to take McCovey’s minor league exploits. Just a half game out of 1st place, they needed an offensive boost and they released terrified AAA pitchers of the specter of facing Stretch. And he went right along treating major leaguers like they were no different, racing to a Rookie of the Year himself (though sadly, after leading the NL throughout August and September that ‘59 team stumbled in the final week of the season to a second place finish — an ominous sign of what was to come). Between AAA and MLB that year he slashed an incredible .366/.449/.723 with 93 XBH and 130 RBIs. These days, of course, the word “slash” has come to be a ubiquitous verb for offensive performance — of whatever stripe. But there’s never been a player for whom the word was more appropriately used. McCovey slashed the ball. He slashed home runs, and he slashed his way into the physical memory of anyone who ever watched that mighty swing uncoil.

“If you pitch to him, he'll ruin baseball. He'd hit 80 home runs. There's no comparison between McCovey and anybody else in the league.”

When I was a very young tot — too small to operate the radio for myself and turn on the game — I’d wait in the evenings on the front porch steps for my Dad to come home from work. And when he did I’d immediately run up and ask him two questions: 1) how’d the Giants do? and, owing to a difficult time getting my mouth around the full name, 2) how’d ‘Covey do? The Giants didn’t always win, but as best I can remember, my Dad always said McCovey had homered — sometimes twice! To this day, I’m pretty sure that 80-home-run season Sparky feared really did happen… somewhere. It lives in my imagination. In the green fields of the mind.

Sparky was right about that. There’s no comparison to ‘Covey. There never was.

On the bench

Brandon Belt, 2010 San Jose/Richmond/Fresno (A+/AA/AAA)

.352/.455/.620, 173 Hits, 43 2b, 23 HR, 112 RBI, 22 SB, 93 BB, 99 K

I’m so sorry, Brandon! Of course, Brandon Belt gets left on the bench for posting what is almost certainly the greatest hitting performance by a Giants’ prospect this century! Who else would that happen to? Brandon showed up on minor league Opening Day in San Jose a totally unheralded 5th round pick who had yet to take a minor league at bat. Within a year he was making Giants fans howl with delight when he was added to the big league roster for the 2011 major league opening day in Los Angeles. How did that happen?

Though he hadn’t played in a game prior to 2010, Belt did take part in fall Instructional League after signing with the team. There coaches gave him a more upright stance that stopped him from cutting off his power. As farm director Fred Stanley was quoted in the following year’s “Prospect Handbook:”

"All we did was square him up and give him some direction back toward the middle. Just kind of freed him up so his hips and hands can work . . . and my goodness."

My goodness, indeed. He spent two and a half months making a run at .400 (with a .500 OBP) in the Cal League before the Giants decided he needed a bigger challenge. Remarkably, Belt produced nearly identical numbers in Richmond (the rocky shores that had shipwrecked so many promising hitting prospects). For the Squirrels he posted 1.036 OPS in a little more than 200 PA before it was time to move again. He managed just a meagre .956 OPS in 13 games in AAA, but he finished the year with a flourish smoking Arizona Fall League pitching to the tune of .372/.427/.616. Belt’s performance led to him being — to the best of my recollection — the only Giants prospect ever listed as a Finalist for Baseball America’s Minor League Player of the Year honor (he lost out to the “better prospect” at the time, Jeremy Hellickson. Bad choice BA!).

I can’t put you over my beloved McCovey, Brandon, but I’ve always been a charter member of Team Belt!

Final Thoughts

And, after all that joyful nostalgia, we must plunge back into the bitter darkness that is the baseball landscape today. It was Black Thursday yesterday. Rumors flew (and more than rumors) of up to 1000 or more minor league players being released yesterday — though there is little transparency taking place on the specifics. Reportedly some teams are waiving as many as 50 players in one fell swoop (we’ll see if that’s accurate). Kevin and I discussed this topic on Pod-Two. As I noted, it was hard to read the tea leaves whether mass cuts were going to make it more likely that the players remaining continue to get paid or less. It certainly sounds like some of the teams who have committed to continuing minor leaguer stipends are among the big cuts.

There’s a logic to it, draconian though it may be. It’s an inevitability that no minor league season is going to happen this year. The draft is abnormally short. Next year if the minors return they will do so in an extremely stripped down nature, with 25% of all teams having vanished from the landscape. Essentially a year’s worth of roster cuts are being telescoped into a matter of hours and days. But unlike most years those outgoing players aren’t going to be counter-balanced with some 60 new players coming in to pro ball (through the draft and the IFA market).

We are seeing just a massive contraction of the talent pipeline and with it the death of a lot of pro ball dreams today. The Athletic’s Emily Waldon summed the situation up with these three tweets from an industry source:

Those with connections to minor league players are hearing a LOT of words like “scared,” “confused,” “uncertain,” “nervous.” It’s a bad mental space to be putting the future of the game’s talent in. One player heading out the door sounded off not just on the layoffs, but on the culture of sacrifice that teams so frequently demand of their young players.

There’s real pain and vitriol in these lived lives. Some of these kids will pursue Indy ball; maybe some will head to foreign nations. Some will coach or teach. Maybe we’ll see some again. But this has been a tough week for so many people.

Meanwhile, the struggle to restart the Major League season continues, with owners trying to spread their losses onto the players after years of keeping their profits to themselves. On that score, Buster Posey said we should read this article, and when Buster speaks, I listen:

One line that jumps out at me:

I’m impressed with the owner’s wanton disregard for fairness and the willingness to create the most hostile dynamic possible with their most valuable assets

In a similar vein, Joel Sherman this morning wrote:

MLB’s first proposal delivered Tuesday was so purpose-pitch brutish that it further entrenched and bonded the players

As Sherman notes, though the sides are focused on how the 2020 season should play out, the 2021 and 2022 seasons (at least) are hanging in the balance as well. There is little to no reason to assume that pro sports will be played in front of large groups of paying fans in 2021 at this point, and after that the CBA runs out. A failure to find common purpose today will impact the game for years to come.

At some point, you have to believe that mutual self-interest will guide the parties into something like a common ground (some nature of deferred payment schedule for the players’ prorated salaries makes sense). At some point you have to believe that the group of owners who aren’t gutting every level of their organizations will begin to assert themselves and steer their colleagues away from the cliff. But it’s hard to see the light of day from the darkness we’re standing in right now.

We hope for the best and deal with what comes.