Topps 1965 series #395

I know I promised that I was going to finally break from my seeming fixation on the 1971 NL West Division winning team. But then I changed the order I wanted go in and followed the traditional scoring system rather than moving physically around the diamond and, well, I ended up with yet another (part time) member of that ‘71 team. Sometimes we just can’t shake our childhoods, eh?

So moving to the hot corner I have both a major leaguer and a prospect-who-flamed-out who I was passionately devoted to. And for good measure, the guy on my bench is a personal favorite too! That makes 3b a pretty great position in which to go seeking amazing seasons of the past. Let’s get after it.

Why Didn’t that Guy Make It?

Starting 3b

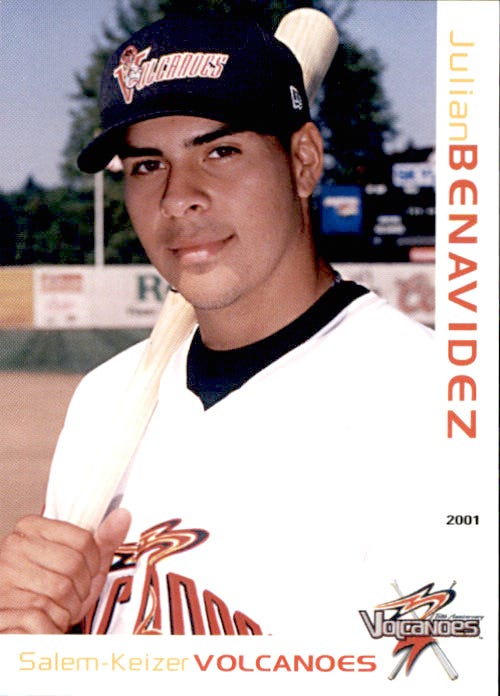

Julian Benavidez, 2001 Salem-Keizer Volanoes (Northwest League, A-), 19 years old

.319/.395/.537, 12 doubles, 9 HR, 39 RBI, 50 G, 24 BB, 54 K

2001 Salem-Keizer Volcanoes Collection #37

In 2002, I had recently moved back to the Washington DC area having spent the previous several years living in San Francisco and Chicago. I was mostly doing freelance work and had plenty of time at my disposal and determined to take full advantage of the Giants recent relocation of their A ball team to Hagerstown, MD. And in April of 2002, there was one player who topped my “Must See” list for the Hagerstown Suns: 3b Julian Benavidez. Now it turned out that 18 year old left-hander Francisco Liriano was really the Must See player of that 2002 team, and I wasn’t even looking at the field when Liriano announced that fact to me — but rather turned back in my chair listening to scout, who’s mouth froze into an ‘ooooooh’ face at the first sight of Lirano’s slider.

But no, the guy I really wanted to see — and I saw a lot of him that year — was Benavidez. Possibly, you’re right now saying “Who?” Well, I’ll tell you: Julian Benvidez was Nate Schierholtz before there was a Nate Schierholtz. He was…and then he decidedly wasn’t.

But like Nate, Benavidez was a high round pick out of a NorCal Junior College (Schierholtz the 2nd round pick in 2003 out of Chabot; Benavidez the 3rd round pick in 2001 out of nearby Diablo Valley). Both were rather rough-fielding 3b. And both were selected after excelling in private workouts at what was then Pac Bell Park, where their power displays tantalized the brass. In Benavidez’ case, he had already tantalized the coaching staff at Arizona State, and the Giants had to spend a sizable bonus to buy him out of that commitment.

But within a few weeks, they were very happy that they had. Because, again like Nate, Benavidez immediately hit the ground running with a fantastic short-season debut. See what I mean? Like twins!

Though the 19-year-old Benavidez was the fifth youngest hitter in the typically college heavy Northwest League, he sure didn’t look overmatched against his elders. The teenager ended the year fifth in the league in batting and OBP and third in slugging. A young, (sort of) hometown, slugging hero to call my very own? Sign me up! Despite having followed enough prospect fool’s gold to know better, I was smitten by the stat line. And I couldn’t wait to see him in the flesh.

Of course, I wasn’t the only one to get carried away in my enthusiasm for the youngster. Benavidez’ Salem-Keizer Manager Fred Stanley, who would go on to be the Giants’ Farm Director for many years, laid a whopper of a comp on him for Baseball America that winter. Benavidez’ approach at the plate and power to all fields reminded Stanley of a young Edgar Martinez. “I know that’s a tough label,” Stanley said, “but to be that young and be able to drive the ball to the opposite field is very impressive.”

Benavidez on an Edgar Martinez path? That…didn’t happen. So what did? I know I said my “Why Didn’t He Make It” tagline was just rhetorical and I wasn’t really going to try to answer the question. Hitting is hard. Leveling up is something even the best players can’t always do. That same BA scouting report that dropped the Edgar comp did note that the 19 year old still had trouble recognizing breaking stuff. And that tracks with the 20 year old I saw in Hagerstown. The raw power was definitely there as he stroked 11 homers and 45 extra-base hits — and yes to all fields. He could hammer a fastball, even decent quality ones. But the strikeouts, which had been slightly concerning in Salem-Keizer (54 Ks to 24 BB in 215 PA) ballooned even further (148 in 522 PA for a 28% rate). But Schierholtz (a much better touchstone than Edgar!) had a year when his strikeouts got out of hand as well (132 for a 25% rate as a 21 year old repeating the Cal League), and he was able to come back from it and forge a successful career. Why wasn’t Benavidez?

Was it just trouble with the curve? Poor pitch recognition? Something in the eyes? Something about the ways his hands worked or didn’t? Benavidez showed excellent power in A ball, he just didn’t ….hit. His average sagged down to .265 and that would be his high water mark for his career. It would continue to drop as he pushed his way up levels finishing ultimately with a .244 average for his career over six seasons.

There’s an old saying in baseball that “hitters hit.” Reductive and tautological as all get out and no doubt the analytically-minded hate the way it confuses outcomes with process. But maybe sometimes it’s just that simple. Hitters hit…and Julian Benavidez quickly found the level where he didn’t hit. Nate Schierholtz went through his adjustments and developments in the minors, he had his struggles, but he always hit (MiLB career .302). It took Nate the Great until the majors to find that level he couldn’t really solve. For Benavidez, as for so many others, it was A ball.

But dang! that kid should have made it.

Future Major Leaguer

Starting 3b

Jim Ray Hart, 1962 Springfield Giants (Eastern League, AA), 20 years old

.337/.403/.526, 182 Hits, 97 Runs, 30 doubles, 18 HRs, 107 RBI, 60 BB 74 K

Hitters hit. Yes. And Jim Ray Hart was nothing but a hitter. One of my earlier memories at a baseball game was seeing Hart lace a double off the fence in Candlestick and watching the entire left-field section of the chain link fence undulate wildly from the impact for much of the following at bat. Unlike Stretch with his long body and long arms, the compact, 5’11” Hart didn’t dazzle you with the fearsome slice of his swing, but there was a condensed violence in that bat when he made contact.

Hart hit everywhere he ever played. Signed out of a semi-pro league in North Carolina for just $1000, Jimmy Ray left a pile of batting championships behind him in his rapid ascent to the majors. I chose his AA campaign — when he bested Richie Allen for the Eastern League’s batting championship — as the representative here, but really his minor league career was a “Pick ‘Em” of terrific seasons.

In his first taste of pro ball as an 18 year old in the Appy League he laid waste to the opposition, hitting .403 with a comical 1.213 OPS before the Giants decided to try to find him a more appropriate level of competition. They never really did. Though he did stumble in the final 30 games of the season in Quincy, Illinois it wasn’t the competition that did it, as he would show in the following years. In 1961 he posted a 1.009 OPS in the California League, finishing third in slugging (.588) and second in total bases behind Robb Nen’s dad, while knocking in 123 runs in 138 games. All at the tender age of 19. The official Baseball Reference page for the 1961 Cal League suggests Hart finished third in batting that year (.355) though multiple references in The Sporting News in the following years attribute the league’s batting title to him. It would not be his last.

Somewhat amazingly, the Giants left Hart exposed to the expansion draft that winter, but the prodigious hitter went unclaimed, perhaps owing to the his defensive reputation which was already extremely poor (and would never get better). It didn’t take the Giants long to realize the risk they’d run however. He’d hit .373 in the Arizona Winter Instructional League that year (something akin to today’s Arizona Fall League gathering the best prospects from each team to play against each other) taking the unofficial title of batting champ. He’d do the same thing the following year hitting .399 while also leading the circuit in HR and RBI. Hart was so feared in the Arizona loop that opposing managers actually devised a shift to try to stop him, putting three fielders on the left side of the infield.

Between those two star turns among the game’s best minor leaguers, Hart turned in a tremendous Eastern League campaign which led his Springfield manager Andy Gilbert to say: “he’ll hit .300 in any league.” For the second straight year he’d banged out more than 180 hits in just 140 games. Over the two seasons combined he’d clubbed 117 extra base hits and totaled 582 bases.

At that point he’d played pro ball for three seasons. Without counting his ridiculous winters in the instructional league, he’d hit .345 and slugged .561 over four levels, winning somewhere between two and five batting titles (depending on how you wanted to count them up).

His triumph over Allen that year, went down to the final day of the season when Hart went 2 for 3 while Allen went hitless to fall to second at .322. The two young power hitters had remarkably similar years. Allen hit two more HRs and two more doubles than Hart, but Hart bested him in Total Bases, 284 to 280. (Hawk Harrelson who led the EL in HRs that year bested both of them with 296 TB). Allen would have his revenge on Hart two years later when he was awarded the NL Rookie of the Year over Hart who had set a Giants record that lasts to this day with 31 HRs.

Ironically, Hart shouldn’t have been a rookie at all in ‘64. After his sensational ‘62 campaign in Springfield the Giants kept a close watch on him the following year in AAA Tacoma, and it didn’t take long to call on him to help a struggling Giants offense that summer. But within days of his debut, an errant fastball from Bob Gibson broke his shoulder and ended his season. So the era of Jim Raaaaay Hart (as the PA would say) would have to wait another year to get going. Perhaps that was an omen of what was to come, as injuries and perpetual defensive issues — that only got worse as he put on weight — turned his career into something of a “what might have been.” Just yesterday (in the “On this day in history” section), I wrote about Hart’s final years with the Giants filled with long stints where he was demoted to AAA despite being an 8-year veteran. Still, nobody who saw him play would remember him as a “what if.” We think of what was. We think of that special crack his bat let loose when he connected. So let’s listen to two men who did see him, Jon Miller and Mike Krukow, pay tribute. “When he hit ‘em they stayed hit.” You’re damn right, Kruk.

On the Bench

Pablo Sandoval, 2005 Salem-Keizer (Northwest League A-) 18 years old

.330/.383/.425, 20 XBH, 50 RBI, 75 Games, 21BB 33 K in 327 PA

Nate Schierholtz, 2004 Hagerstown/San Jose (Sally, Cal, A/A+), 20 years old

.296/.347/.523, 146 H, 67 XBH 18 HR, 85 RBI

Courtesy of the Salem-Keizer Volcanoes

I’ve been sadly neglecting the Dynasty Era Giants in these retrospectives — not because I want to! Though I’ll admit my failure to even mention Buster Posey’s 2009 season in the Catcher post was unconscionable. So let’s make up for that with a two man bench at the hot corner.

Of course, I’d prefer to use Sandoval’s scalding hot 2008 year, when he hit .350 with a .972 OPS between San Jose and Connecticut, more than doubling his career HR output with 20 (he had 15 in his previous five years combined). And that was just in the minors, he finished out his year by hitting .345/.357/.490 in a San Francisco debut that was exactly 4 PA too long to allow him to qualify as a rookie in 2009 (when Chris Coughlan was awarded the NL ROY in one of the weakest classes on record). But no, I can’t use 2008 for Pablo because that was one of the two years he played absolutely no 3b (the other being his AZL campaign in 2004). So we’ll have to settle for his year with the Volcanoes when he played 70 of his 72 games at the hot corner, showed his excellent contact skills (with a K rate below 10%) and put up some seriously good numbers for a teenager in NWL. An afficianado of the importance of age/level, that was the year I glommed onto Pablo’s prospect status, and I would beat the drum for him tirelessly on Giants’ prospect sites through the down years that followed. (Ha! They weren’t ALL Julian Benavidezes!)

Nate would make a fine backup based only on the torching he gave the Sally league that year. Though even then his days as a 3b appeared numbered, he bashed the Sally with a vengeance, hitting 15 HRs by Memorial Day and earning a promotion to the Cal League before June 1. I sat on what turned out to be his final homestand in Hagerstown that year, when he had three walk off hits within a week — two homers and a triple off the top of the wall. It was an incendiary performance. Oddly, his power stroke didn’t seem to accompany him to San Jose as he’d hit just 3 HRs in the Cal League over the year’s final three moths. Though otherwise his stat line was quite similar to his Hagerstown line. By the following spring (when he repeated the Cal League), the Giants had bowed to the inevitable and moved his rocket arm to RF where it would stay.

Still, Farhan should be happy! My 3b bench includes a Catcher, an OF, a 2b and a relief pitcher. Pretty versatile!

On this Day in History

Since today is Juneteenth, it’s only fitting that I end this piece by noting that Jim Ray Hart, like Willie McCovey, Willie Mays and so many others of the great Giants of my youth, grew up and suffered under the indignities and injustices of Jim Crow. And think about the excitement and hope they must have felt when the Civil Rights Act was signed into law. And reflect on how badly we’ve failed to live up to the principles encoded in that, and so many others of our laws.

The Angels brilliant young prospect Jo Adell wrote a heartfelt, eloquent post in The Undefeated on his experiences with racism in this country. Included in that piece, he takes an entirely justified shot at the racially coded language that still lays at the heart of so much baseball scouting language. Why am I the “toolsy” “raw” “high risk” player, Adell writes, while my white counterparts are praised for their high “baseball IQ.” These code terms for player skills sprang up in the immediate aftermath of integrated sports and have lived a long, full, insidious life in sports writing ever since. I’ve certainly done this myself without thinking and I ask each of you to call me out on it if you see me falling into these lazy word patterns in the future (I’ll tell you the truth, I originally started this sentence by describing Adell as “shockingly talented” which I realized then fell into the same patterns, and then went back and settled on “brilliant” as a good description of both watching him play and reading his article). As Jeffrey Paternostro and Jarrett Seidler wrote today for Baseball Prospectus, we can all do better. Our past is prologue, but it doesn’t have to be our future. But things won’t change without effort, care, and action. Today’s a good day to read, to listen, to watch, to learn and to dedicate ourselves to working for a better future.