All Time Minor League Seasons: RP

Let's revisit a moment of historic importance

1965 Custom Card

It feels like each time I begin one of these installments, I start with an announcement that I’m changing my planned design, as if there were ever any established order moving things along here. That disarray continues today, as I drive completely off the range — at the wheel of the bullpen cart! The start of the Nippon Professional Baseball season has spurred me to change directions again and tell a tale I’ve been itching to get to since I first conceived of this series.

There are surely many reasons why players failed to build on the successes of great minor league campaigns — injuries are often the culprit, maybe some didn’t have the ability to deal with failure or have the right work ethic. Most, surely and simply, were overcome by the exponential challenges posed by the levels of pro ball. But today we have an absolute one-of-a-kind story for why our player didn’t quite “make it” — cultural misunderstanding.

Why Didn’t That Guy Make It?

Starting(?), uh, CLOSER: Relief Pitcher

Masanori “Mashi” Murakami, 1964 Fresno Giants (California League - A), 20 years old

11-7, 1.78 ERA, 0.92 WHIP, 159 Ks, 34 BB, 106.0 IP

I have a very strong memory from my youth, that whenever Masanori Murakami’s historic contributions to baseball were mentioned on a Giants’ broadcast — for whatever reason — the same clip of him stepping forward and tipping his cap would be shown. Possibly that was professional newsreel footage shot at the same ceremony this amateur home movie comes from, honoring the very first Japanese player in major league history.

The footage I remember so vividly doesn’t seem to exist on You Tube anywhere. There are photos, including one with Orlando Cepeda in the locker room that I also remember seeing alot. And there appears to be extant film of exactly one pitch that Murakami threw in the majors, which you can see at the 2:54 point of this commemoration video put together by the Giants (the whole thing is terrific):

But I’m getting off my story here. Inevitably, along with the clip would come the chyron that announced that Murakami had pitched for the Giants for parts of the ‘64 and ‘65 seasons. As a young, apparently uninquisitive tyke (and decades away from the existence of Baseball-Reference) I would think to myself: “two years, huh? Guess he wasn’t very good.” Well Small Roger, I would like to take this opportunity to publicly inform you that you were very, very wrong to assume so. Mashi, as he was known, was fantastic.

Ironically, it was only the promise of coming to America that enticed Murakami to turn pro in the first place. He hadn’t intended to. Both he, and his father (who hadn’t approved of him playing ball in high school at all) wanted him to go to college. So when the legendary Kazuto Tsuruaoka, manager of the Nankai Hawks (and record holder for most managerial wins in the NPB) tried to sign Murakami, off his High School team’s back-to-back National High School Tournament championships, the answer was “No.” But Tsuruaoka had one more enticement. If Murakami signed, he would be sent to the United States. As Murakami himself explains in the video below, to a kid who spent every Friday night watching “Rawhide,” that was an offer too good to be turned down.

What Tsuruoka was really thinking at the time is unclear — there was no agreement between the NPB and MLB at the time. And in fact, Mashi’s first year in pro ball was spent in Japan’s minor leagues, ending in a debut in the NPB that didn’t go all that well. He allowed a HR in his two innings and also hurt his elbow.

But over that winter, an innovative agreement was forged between the Hawks and the San Francisco Giants. Three Japanese players would be sent to the US for minor league development. The three players were all young, just 19, and none of them were considered to be particularly good prospects at the time. In fact, two of them, 3b Tatsuhiko Tanaka and C Hiroshi Takahashi, struggled with American ball and returned to Japan part-way through the season.

But Murakami was a sensation. The kid who dreamed of coming to America found himself very happy here — despite the fact that what he mostly saw of the country was Fresno (I kid, I kid, I’m a Tulare County native myself!). He loved the cars, he loved driving around and seeing the city. He was an explorer who had found his destination.

And on the field, he was a revelation! The left-hander simply over-powered the Cal League as Fresno’s relief ace. He struck out 13.5 batters per 9 innings and had an incredible 5:1 K to BB ratio. For a pitcher who ran up huge strikeout totals, the left-hander wasn’t a power pitcher. He brought precision and control, as well as a deceptive side-arm delivery. And while it seems he’s commonly said to have thrown mainly a slider or curve, his own description of his repertoire included both a curve and a screwball! A deceptive pitcher with command over two separate breaking balls that broke in opposite directions? Yeah, that’s gonna work. Even better, as Murakami noted, it was easier to pitch to American batters because, “in Japan batters only swing at strikes. Here they try to hit everything out and they don’t care if it’s a strike or not.”

Mashi’s Cal League season was capped with a masterful performance when he struck out 9 of the 12 batters he faced to clinch the Cal League pennant for Fresno. That gave him 159 Ks for the year in just 106 innings, to go with a 1.78 ERA. That convinced the Giants, who were trying to run down the Phillies for the NL pennant, that maybe Mashi could help.

The 20-year old made his major league debut on September 1, 1964 in Shea Stadium — the first Japanese player ever to do so. That debut came at the end of a madcap day. The Giants gave him a plane ticket to NYC but had no one there to greet him. The youngster who spoke no English had to find his way from LaGuardia to the team’s hotel — where he discovered no reservation in his name. When he finally found a member of the organization to help get him to the stadium, the Giants realized that they had to sign him to a major league contract before he could pitch, and were (by some tellings) forced to locate a fan in Shea who could speak Japanese to get this final detail accomplished. After all that excitement the actual game — scoreless inning, two Ks — must have seemed anti-climactic. Though he would long remember the feeling of being announced into the game: "Now Pitching for the Giants: Mashi Murakami.”

Murakami would go on to pitch 15 innings that September, allowing just 3 runs and continuing his dominance of the strikezone with 15 Ks and just 1 BB. The Giants had seen enough. Their contract with Nankai included a provision that would allow them to purchase the contract of one of their developmental players for $10,000. Or at least, that’s how they read the contract. Thrilled with the youngster’s work they wired $10,000 to Nankai and signed Murakami to a deal for the 1965 season.

And that’s when the drama began. One would presume that the Giants had a very limited understanding of Japanese culture or the nuances of Japanese contract law — and perhaps limited concern for it, as well. By some accounts Nankai had intentionally provided players for development who had no chance of inspiring MLB contracts. And there were those who believed that Murakami’s success (and popularity) took Nankai by surprise — and they moved belatedly to ensure that they, not San Francisco, would be the beneficiaries. Given the way major league baseball has plundered other cultures, the NPB was no doubt wise to view the possibility of becoming an MLB talent mine with a jaundiced eye.

From Nankai’s perspective, they had fulfilled the terms of the developmental deal by providing Murakami’s services for the summer, but he was under contract to them for 1965 (Japan, too, operated under a “Reserve Clause”) and thus in no position to sign a deal elsewhere. He had been farmed out for a year and that year was over. The $10,000 were presumed to be a bonus for services most excellently rendered. Pressure was put on Murakami to return home. His father, who had always wanted him to be a doctor, not a ballplayer, publicly noted that he would never have allowed his only child (a teenager and thus a minor under Japanese law) to leave the country for good.

As communications between the parties became increasingly embittered, Nankai claimed that Murakami’s signature on San Francisco’s contract was a forgery and pointed out that the original contract included a “homesick clause” for players who weren’t able to make the cultural transition and that Murakami was, indeed homesick. The squabble escalated to the level of Presidents of both leagues, with Ford Frick angrily canceling a planned showcase trip to Japan by the Pittsburgh Pirates.

It was the NPB President, Yushi Uchimura, who finally brokered a compromise. Murakami would be allowed to return to the US for one — and only one — season. He would pitch for the Giants for the 1965 season (which was already three weeks old by the time the compromise was agreed upon) and then he would return home for good. In that lone season, the 21-year-old left-hander from Japan was outstanding. Though his 3.75 ERA was just average, he was once again a highly successful strikeout artist, striking out 85 batters over 74 IP while walking just 22. His 1.1 rWAR was the sixth best on the staff, and second best in the Giants bullpen, while his 2.81 FIP was second best on the team behind only Juan Marichal. Mashi was a significant part of a 95-win team (that once again finished 2nd to the Dodgers).

Though he would go on to a long and successful career in the NPB, Murakami would always harbor regret at what he might have become had his MLB career been allowed to grow and flourish. Indeed, if you want to read much, much more about Murakami’s life and career, the place to go is Robert Fitts 2015 book on the pioneer, which is subtitled: “The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami.” As he himself said in the video interview above, though he did the honorable thing at the time, looking back he regretted his decision. (By the way, in that video the host asks him whether the original intention was for him to return to Japan after just a few months — he gives a long answer to that question only in Japanese. So if anybody out there speaks Japanese, I’d love to know how he answered that question). Murakami lost his dreams for an American career; San Francisco lost possibly an icon, as well as a talented arm.

It would take 30 years for another Japanese player to come to the US, and no doubt the hard feelings that both sides had over the bitter negotiations for Murakami’s service played a role in that long delay. “Why Didn’t That Guy Make It?” In Murakami’s case, the answer was: he was so good that two different countries wanted him. And one had a claim on him that the other couldn’t equal.

Middle Innings Guy

Michael Broadway, 2015 Sacramento River Cats (PCL, AAA), 28 years old

48.1 IP, 0.93 ERA, 64 K, 8 BB, 0 HR

PCL batters were simply helpless vs. Broadway’s slider in 2015. Over 20 appearances between May 15 and August 4 he allowed a total of 1 run and just 5 HITS! He allowed runs in just five of the 40 games in which he appeared, and never allowed 2 runs in a game. He struck out 37% of all batters he faced while walking just 4.5%. That mastery didn’t extend to major league hitters, but for a magic summer in Sacramento, Michael Broadway was untouchable.

Future Major Leaguer

Closer

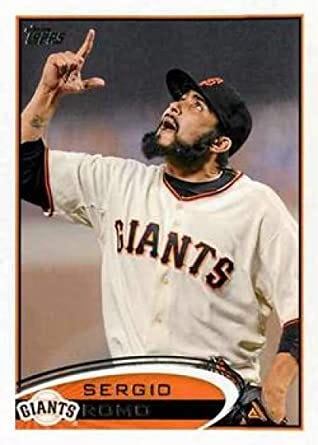

Sergio Romo, 2007 San Jose Giants (California League, A+) 24 years old

1.36 ERA, 66.1 IP. 106 K, 16 BB, 10 ER

2012 TOPPS Series 2 #379

I recently wrote a fairly long appreciation for Sergio elsewhere, so let me just crib from myself here, if you don’t mind:

By and large, the Great Giants of the Decade came with fairly substantial prospect sheen on their way up. No, this isn’t comprehensively true, but most of the team’s stars came with pedigree: 1st round picks like Timmy and Buster, MadBum and Cainer, high round picks who developed into Top 50 prospects like Brandon Belt and Hunter Pence. Even Brandon Crawford was a known dude coming out of high school who many expected to develop into a 1st or 2nd round pick (he eventually dropped to the 4th).

And then there was Sergio Romo, the undersized kid from the southern tip of the Salton Sea in Imperial Valley — as close to nowhere as one might ever find themselves and still be in California. Romo, whose college career wound from Orange Coast College to Arizona Western JC, to Alabama State, and finally to Mesa State College in Colorado where the Giants spotted him and used the 852nd pick of the 2005 draft (the year the Giants infamously maneuvered to intentionally lose their first round pick) to select the skinny, short, right-hander with more guts than stuff, who, yes, only looked illegal.

But that’s getting ahead of ourselves.

For a 28th rounder without a blazing fastball, Romo made fairly quick work of the minor leagues. It took him almost exactly three years from draft date to major league debut. He came to San Francisco as part of the original Churn, the great cattle call of 2008, that amazing season that also gave us the debut of the Kung Fu Panda, the Giants’ first Cy Young winner in 40 years, and a draft class that included Buster Posey and Brandon Crawford — solid amount of entertainment value for a season that opened with Brian Bocock and Jose Castillo in the lineup.

Romo finished his minor league career with a minuscule 2.36 ERA over 293 IP, with a ridiculous 333 Ks to just 55 BBs. He started out with strong performances as a starting pitcher in Salem-Keizer and Augusta. But he took his performance to another level once he was moved to the bullpen, including a year for the ages in San Jose where he posted a 1.36 ERA over 66 innings while striking out an absurd 106 batters and walking just 15. That combination of high K/low BB rates nicely summed up Sergio’s greatest strengths: for a guy with a pedestrian fastball he attacked hitters relentlessly in the strike zone with excellent command, and he proved incredibly hard to hit.

In fact, Romo wasn’t just hard to hit, he made major league hitters appear downright foolish in the attempt:

Andy Baggarly made the point on a recent Baggs and Brisbee podcast that Sergio Romo is exactly the kind of guy we’re going to lose from the game as the major league draft gets smaller and smaller (Jim Callis, among others, believes we aren’t likely to see all 20 potential rounds next year and probably we won’t see more than 20 ever again). Yes, most of the players selected in rounds 15-40 are unlikely to see the high minors, much less the major leagues. Heck that’s true of rounds 3-14, too, while we’re at it. But while we close the door on the dreams of fringe-A ball players and Indy League kids, we’re also losing out on guys like this: the over-achievers who bounce from Brawley High School, to JC, to small colleges in the middle of nowhere who just keep getting guys out. Out and out and out and out until the guy you’re getting out is suddenly one of the greatest right-handed hitters of all time, and you’re celebrating the final out of a World Championship. That’s the type of sacrifice to the game that owners like Arte Moreno and his clique are willing to make. Let me say right here and now that it stinks and it’s not worth it. We need all the Sergio Romos in our game we can get!

Middle Innings

Russ Ortiz, Bellingham and San Jose Giants (NWL/Cal Leagues, A-/A+), 21 years old

0.67 ERA, 40.1 IP, 62 K, 15 BB

The journey that took Russ Ortiz to a mound in Anaheim where he came thiiiiiiiis close to being the winning pitcher of a World Championship-clinching game took an amazing twist in the summer of 1997. That’s when the Giants took it into their heads that their star closer prospect might possibly make a decent starting pitcher. Ortiz had always been a closer. He was a closer for three years at University of Oklahoma, and for the first two years of his pro career, he was a closer with the Giants. And a great one! Over those two years, during which he rose from short season ball to AA, Ortiz struck out 154 of the 423 batters he face (37%). He allowed just 16 earned runs, 12 of them in his 26 inning stint in AA. He allowed just 1 home run over those two seasons, had a WHIP just a whisper above 1.00 and walked away with 47 saves in 90 games.

And just as he was on the verge of being big league ready in the spring of ‘97, Brian Sabean looked at him and said: “I think this kid could be a starter for us.” Good job, Scout-y Sabes! Yet another reason why that man should be in the Hall of Fame (though crying after Travis Ishikawa’s pennant winner is a definite factor in his favor as well).

Final Thoughts

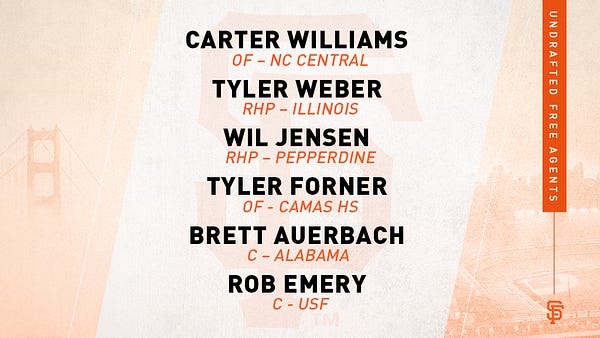

I’m going to write a comprehensive wrap-up of Non-Drafted Free Agents the Giants have signed sometime soon after they’ve had a chance to bring a few more aboard, but just to keep everyone up to date, they’re currently up to six players signed since the draft:

So just file those away in your memory box for the time being. Also, this:

We got ourselves a new B-Craw! (Or maybe Mauricio Dubon was the new B-Craw and Jimmy Glowenke was the new Dubon and now Emery is the new Glowenke?)

On a more serious matter, Andy Baggarly got THE quote from Farhan Zaidi on the abominable behavior of an elected official in the Giants home away from home and I have to say, his thoughts here are one of the first times I’ve really stood up in my chair and applauded Farhan since he came onboard:

And lastly, before the Giants submit their official list, I’ll go ahead and take my stab (sure to be wrong) at what the 60 names they turn into MLB this weekend might be:

40-man Roster

Melvin Adon

Shaun Anderson

Tyler Anderson*

Tyler Beede (moved to 45 Day DL)

Sam Coonrod*

Johnny Cueto*

Enderson Franco

Jarlin Garcia*

Kevin Gausman*

Trevor Gott*

Jandel Gustave*

Dany Jimenez*

Reyes Moronta (IL, but not 45 day)

Wandy Peralta

Dereck Rodriguez

Tyler Rogers*

Jeff Samardzija*

Sam Selman*

Drew Smyly*

Andrew Suarez

Tony Watson*

Logan Webb*

Buster Posey*

Aramis Garcia (45 day IL)

Abiatal Avelino

Brandon Belt*

Mauricio Dubon*

Wilmer Flores*

Evan Longoria*

Chris Shaw

Donovan Solano*

Kean Wong

Jaylin Davis*

Alex Dickerson*

Steven Duggar

Joe McCarthy

Hunter Pence*

Jose Siri

Austin Slater*

Michael Yastrzemski*

Taxi Squad

Trevor Cahill*

Seth Corry

Tyler Cyr

Sean Hjelle

Trevor Oaks

Tyson Ross*

Andrew Triggs

Nick Vincent

Raffi Vizcaino

Joey Bart

Rob Brantley*

Tyler Heineman

Zach Green

Marco Luciano

Darin Ruf*

Yolmer Sanchez

Pablo Sandoval*

Hunter Bishop

Alex Canario

Billy Hamilton*

Luis Matos

Heliot Ramos

* On 30 Day OD Roster

I’ve added two extra members of Taxi Squad (22 total) but I’ve made room for them with 2 members of 40 man shifted onto the 45-Day IL (replacing old 60-Day for 2020). Probably my addition of Canario and Matos is going a bridge too far, but I want them dangit! (I want Toribio, too for that matter). What are your guesses? Let me know below!

We’ll sift through the full roster of names on Monday. Have a great weekend everyone!

After watching Broadway blow away the PCL in early 2015, I described it as "like watching a polar bear fight a taco."

I stand by that.

I loved your telling of the Murakami story, Roger. Really well done. 1965 was the first year I collected baseball cards, so you’ve recently been speaking directly to some of my fondest memories. It’s nice to know that my young perception of Masanori wasn’t wrong - he really was as good as I perceived, I recall being so proud that my Giants had gone all the way to Japan in their hunt for talent. I assumed at the time that there was a Japanese American contingent in SF that would be welcoming and justifiably proud - I wonder if anyone can confirm that?