I’ve been thinking about this piece for some time, and it feels right somehow to get to it now. I’ll return to my typical Giants-centric content next time with some draft posts. But for now, if you’ll indulge me…something personal.

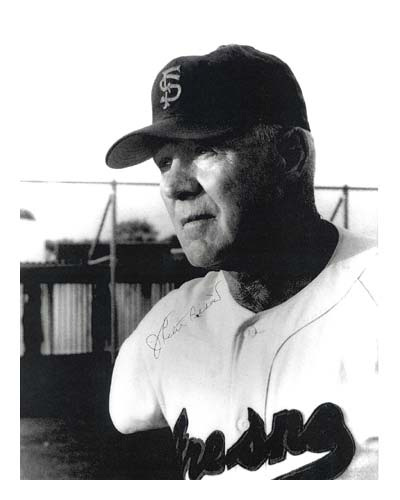

I met Pete Beiden when he was, I guess, 71 or ‘2 years old. He was already more than a decade retired from one of the legendary careers in West Coast baseball. That career was memorialized in the field that bears his name at Fresno St. where he led the Bulldogs to ten conference championships and more than 600 wins (including a .691 career winning percentage) over two decades of coaching. The 1959 Bulldogs went an amazing 49-13 and finished third in the College World Series.

But retirement didn’t suit Pete — he had more to give — so he spent his senior years assisting Bert Holt, an old pupil and friend, at the College of Sequoias in Visalia. And there in the San Joaquin Valley heat, that seemingly fragile old man with a deceptive and unquenchable strength that came from somewhere unseen would stand at the grass cutout behind 2b and hit fungos for days.

The fungo was a permanent attachment for Pete. It was always poking out of the bed of his pickup when he drove up and it was always in his hand while he was on the field. He was a maestro and the fungo his baton. He once told us that if he knew it was coming, he could hit anybody’s fastball while doing a jig. And then — to demonstrate the importance of disrupting a batter’s timing — he did exactly that, twisting around in the batters box to some crazy jitterbug of a dance from the distant past and then flashing the ubiquitous fungo bat and barreling up heat from a 20-year-old kid who would be drafted by the Yankees later that summer (and who caught a lot of flak in the locker room later that day).

He had a specific drill he’d run with the outfielders — of whom I was one. Pete would hit fly balls that skimmed off the OF wall on the way down. Now and again he’d clang one off the top of the fence. Very occasionally one might sneak over and land among the trees that protected Noble Avenue. If you caught the ball at the front of the warning track or in the grass of the outfield it was a rare enough misfire that trash talk and laughter would break out and Pete would berate himself in that gravelly, barely discernible form of quasi-jibberish that characterized what everyone referred to as Beidenese (in Beidenese no one had a personal name — everyone was either a “lad” or called by the name of their high school; “doofloppers” and “sandblowers” and “hot dogs” colored most every sentence the man spoke). But mostly, fungo after fungo, day after day, he would careen fly balls of perfectly ordinary height that exactly grazed the wall upon completing their arc. Precisely so. Because, of course, Pete had something precise to teach us.

…

Probably because I’m both a baseball fanatic and a film buff, it always struck me that Pete was like something out of a Frank Capra film — a Frank Capra baseball film (which now that I’ve written those words out loud, certainly seems like something the universe should have given us). John Peter Beiden was born in Dinkel, Russia in 1908 and with his parents and six of his siblings (seven more would stay in Russia) moved to the Fresno area in 1912. A star athlete for Sanger High School, he would earn an athletic scholarship to Oregon State, but would choose instead to follow his High School coach down to Redlands University. An older brother stayed home with their father and worked so that Pete and his brother Hank could go to college and play ball. Of course, they won a baseball championship there too — the 1931 SCIAC title. See what I mean? Totally, Capra-corn movie stuff. He became a player-coach as a Catcher in the Cubs system and in 1948 was offered the job of managing the old Hollywood Stars in the Pacific Coast League. But on advice from his wife Martha, the great constant of his life, he turned the pros down and instead accepted the job that would define his career at Fresno State.

I should say, I didn’t know most of these things about Pete — I had to look them up. In fact, at the time I knew relatively few details about his life. Though I listened to him talk for hours on end, I rarely asked questions (no doubt some personal combination of innate shyness and teenage callowness prevented me from prying into his fascinating life). But I was transfixed by the way he looked at the game. I was a scrub on championship contending team (the pain of that final loss is a whole different story). My primary value to the team was providing batting practice fodder for a hard throwing right-hander who was too wild to allow into games. And because I never dented a blade of grass on the field during regulation games, I had plenty of time to listen to Pete talk ball — listen to a man who used to call Branch Rickey “friend” and who no doubt shared many thoughts on the depths of the game with that legendary Hall of Famer. All these decades later I still feel like everything I know about the game — everything I’m still learning about the game — I was taught first by Pete.

I was decidedly NOT one of those 75 or so people subscribing to Bill James’ original Abstract advertised in back pages of The Sporting News (no, my eyes were caught by a different ad that sent me subscribing to early copies of Allan Simpson’s new Baseball America instead). I didn’t really come into contact with “Sabermetric” concepts for several years — probably finding Pete Palmer and John Thorn’s great Hidden Game of Baseball in a wonderful old used book store in Copley Square in late in the 80s was my real entry drug. But when I did come across the “new ideas” that soon enough started roiling the baseball world with fierce and bitter “old school” vs “new school” factions — what first impressed me was how easily I connected these concepts to the things that Pete Beiden had taught me.

There was always such quiet logic he was working out. The game was so simple but needed constant observation to maintain. There was a mantra he taught me that I have repeated every summer since: “Take outs quicker than you make outs.” The formula for being successful in baseball was really just that. Take outs quicker than you make outs. It was simple; it was easy to remember. It rhymed and everything! But the implications were immense.

It may sound blasé today, but listen, this was a revolutionary concept to me, an 18 year old muttonhead — excuse me, lad — blossoming in late-1970s-era America. It was the first time anybody had so clearly expressed to me that the coin of the realm, the key to the castle, the meaning around which all else circles in baseball, is outs. I had always breezily accepted the notion that there was no clock in baseball. Pete was the first person to turn me on to the opposite notion — there is a clock and the unit of measurement that it ticked down was “outs.”

Even more extraordinary — there wasn’t just one clock, there were two! Yours and theirs. And your role on the field at all times was to try to speed them up or slow them down. Slow your clock down while you speed their clock up, and success would be yours more often than not.

This had all kinds of ripple effects and dimensions. I remember once someone mused that teams having really good seasons always seemed to have guys having out of nowhere career years. Naturally, Pete said — career years go together in baseball because that was the way the “outs” clock worked. With a clock that ticks off seconds every play, every shot, every handoff, every scoring opportunity was in some greater or lesser degree a zero sum game — an opportunity for one player that would never be granted to his or her teammates because the time was gone. So when, say, Jerry Rice was busy having a mind-blowing record-setting season, it was certain to come at an expense of opportunities to his teammates.

But in baseball, just the opposite happens. Because every time a player did that most essential thing — not make an out — they put time back on the clock and granted one bonus opportunity to a teammate. In no other game was one’s own personal success also a gift to teammates — a chance for their personal success as well. So big years, career years, blossomed together in baseball in a way that was virtually impossible in other sports. It was in the very architecture of the game.

Which gets me back to that fence drill, the purpose of which was to figure out exactly how shallow you could play while still being able to defend the yard. We would run back to the fence over and over and over again to learn just how much ground we could cover, precisely how much, to the inch practically. And just how long that took us. If the ball was in flight three seconds, we needed to know how far we could travel in that amount of time (assuming proper read and routes, of course). The point of that drill was to get to the fence when the ball did and not long before. Standing and waiting for a ball to come down was pure waste to Pete — and there was little on a field he hated more than wasted motion. “That ball was up in the air for 4 seconds!” he once grumbled at me “do you know how far a [grumble grumbledy] hotdog ought to be able to run in 4 seconds?” And we should know — we should know exactly!

Understand, we were in essence computing something. We were modeling. We didn’t have computers (I did have a computer programming class that semester — we would create shelf long rows of punch cards to produce some basic math equations, and during the final exam a student tripped carrying his shelf to the teacher and spilled months of work on the floor, irretrievably gone). So instead we had to do the computing, with our bodies, with our powers of observation, with carefully repeated actions over and over, varied ever so slightly. Could I play here, or just one step further in or over….here.

If you knew exactly how long it took you to get to the wall, exactly how much of the field you could cover in the three or four or five seconds of hangtime — then armed with that knowledge you could position yourself to try do that most essential thing you could do on defense: take away outs. Home runs were going to be home runs. Liners off the wall or down the line…well… a lot of doubles were going to be doubles. But converting potential line drive singles into outs — that was an avenue to impact games greatly. Pinching off liners in the gap — that was a way to take away bases (not as good as outs, but still good!). If you could position yourself in a way that allowed you to convert the occasional sinking line drive single (or even double) into an out you were turning knowledge into a competitive advantage. We didn’t have advanced knowledge of batters hit profiles (other than reading swings). So we had to utilize advanced knowledge or our own abilities. Take outs quicker than you make outs.

Pete’s eye for details like this was extraordinary. He was a master at reading body language — he didn’t just want you to cut base corners as thinly as possible, he could explain to you the mechanics for making your body do it. He worked with us on when exactly we should get our feet moving pre-pitch (it was different for everyone) so that our weight was perfectly balanced to move in any direction upon the swing. And to read swings so as to be moving prior to contact. He couldn’t abide baserunners who failed to read balls to the outfield well enough to take an extra base (“that [grumbledy grumbledy] ball a mile away from that sandblower!”). He talked at length about the game within the game — the battle between pitcher and batter to determine which one of them would control the at bat. The pitcher’s job was to make you swing at his pitch and the batter’s job was to not do the pitcher’s job for him.

All of these connected so smoothly in my mind to a sabermetric, data-oriented view of the game. And all of them I learned from a man who had been born in Czarist Russia before the world had ever heard of Vladimir Lenin, much less Bill James. Even pitch framing was old school to the old Catcher . He had his own ways of expressing it, of course — “stay quiet back there,” “sit in the cradle,” “show him the pill” — but he was talking always about the fundamentals of catcher framing. Fundamentals that his future brother-in-law (another Russian emigreé) had taught him back in the time of World War I.

At the time I was enraptured listening to Pete talk because when I listened I felt connected to baseball’s past — this man was friends with Branch Rickey, he fought with Casey Stengel for poaching his players. He saw DiMaggio play as a minor leaguer! Ironically, in the decades since I’ve always felt that Pete was connecting me to baseball’s future. Not that he — or I — envisioned the way Big Data was going to come to rule our world or our game. But no “new” concept has ever seemed really foreign to me because there was always a root principle of Pete’s to connect it back to. Don’t get me wrong, we stole bases back then, and there were even a few sacrifice bunts (which was the world’s BEST way to take outs; get an early lead and you could just start collecting outs like candy). But the deeper meanings — the places to look for edges that could help you beat your opponent — these have always felt like something I’ve heard before and I always know who I heard it from first.

I knew Pete for such a short time — five months, maybe, one spring 40 years ago. But a season hasn’t gone by since in which I haven’t thought about him.

All of which is tinged with a morsel of regret. And that’s I suppose that’s why I wanted to write this piece. There’s no particular reason for me to tell you about this long ago legend — there’s many others who could probably recount all this as well or better than me. There’s still a lot of Pete’s disciples, or disciples of disciples, hanging around the game even at this late date.

No. I suppose I told you all of that because I wanted to tell you this. I wanted to tell you about the last time I ever saw Pete Beiden. I don’t remember clearly when it was, whether it was just after the season ended or maybe sometime in the summer months when I was on campus for football practice. I do remember exactly where I was and who I was with — standing next to the student parking lot with two friends of mine from high school — when Pete drove up in his white pickup truck with, naturally, shovels and fungoes hanging out the bed.

Seeing my friends and I, he walked over to say hello. He asked if I’d be returning to the team the next year and I said I wouldn’t. I shouldn’t have gone out my freshman year — I was much better at football and skipping spring practices had only put me at odds with the football staff. Pete nodded his head and said earnestly, it was too bad, he’d miss me. Then taking my arm he turned to my friends and said earnestly: “this lad didn’t have the talent of anybody else on that team but he worked just as hard as everybody else and harder than most. He came to the field every day, early, and ready to go.”

He paid me, in other words, a genuine and I’m sure sincerely felt compliment — the only one he ever paid me that I can recall. And in response, I turned away. I just… couldn’t hear it. Couldn’t hear that he was imparting another lesson. I hear it now, of course, now that I’m much closer to Pete’s age. But at the time when I needed it… at the time all I could hear him saying was that I wasn’t good enough. I didn’t really understand what virtues he was saying were meaningful to him. I understood that I couldn’t play. Worse yet, this harsh truth was laid out so frankly in front of my friends — the horror of being “found out” by one’s peers tore at me. Of course, most every player hears this truth at some point, or comes to know it regardless. The game tests you. And it always wins.

I tried to mask my embarrassment. I muttered something more incoherent than the most inscrutable Beidenese and I ended the conversation as quickly as I could. He nodded, satisfied, said goodbye and walked on. In the last moment I would ever have to thank him for all he had given me, I literally turned my back on the man. And now, of course, I wish I’d thanked him more than I’ve ever wished I’d done something extraordinary on the field. I wish I had the time back again to thank the man. And I think about how we can mistake each other, even within those bonds that should tie us closest together.

Really great! And for what it's worth, I think that you have the right read on the good intent behind the praise that he gave you in your last interaction. However, if he delivered it as you said, then there's some fault on his side, too. I feel that, if you want to truly give a compliment or advice (or both at once), it's in large part your responsibility to meet the recipient where they can receive it correctly, otherwise what's the point.

Wow. Thanks for this, Roger.