A really enjoyable by-product of my “On This Day in History” segments I’ve been appending to most posts has been re-discovering the lost, forgotten or previously unknown (well, I guess that would be just regular “discovering”) seasons of amazing accomplishment. While I’ve tried to highlight stories here or there that catch my eye, the confines of a single date obscures larger narratives working in the background. There’ve been so many “ah ha” moments, and even a few “whoas” when coming across the players who achieved — if only for a time, if only for a summer — true greatness. There are seasons that need to be remembered and celebrated. The seasons where players felt magic flowing out of them like it would never stop. For some, it would never come again, while for others it was just the beginning of a long ride. Regardless, I found myself hooked by these seasons of great promise and decided that I needed to be the one to chronicle them.

Of course, the first thing I needed to do was set myself some rules. There are two obvious categories that the great seasons fall into: guys who went on to successful major league careers (of some stripe) and then the guys you built up great hopes for who, for whatever reason, just stalled out — the All “Why Didn’t that Guy Make It?” Team! [Note: this is a rhetorical question, I’m not actually going to try to solve the mystery of why they all didn’t make it, in large part because the “reason” is the self-evident one: it’s damn near impossible to make it!]

Some of these guys you’re gonna know and remember fondly; some will be new discoveries for you (as they have been for me). Just to set expectations, I’m not going to be fundamentalist about this — when I say “why didn’t that guy make it” I’m not talking about players who never saw the majors at all. Thomas Neal counts here!

But guys who don’t count? Nate Schierholtz doesn’t count — his career may not have blossomed quite how we hoped but Nate was a valuable role player for multiple teams over 8 years. Did you remember that Jacob Cruz had a 9-year career, or that Gary Alexander had a 7-year career? How about Jack Taschner? Six years he was in the bigs! None of them count on the “why didn’t he make it side;” they’re all successful major leaguers. Travis Ishikawa had 120 games and 363 PA in a single year (not to mention one immortal moment)! He doesn’t count. Of course, since these are my own rules, I will feel free to disregard them totally whenever I really need to tell a story!

As for the All Star Team of guys who “made it” — well you may be shocked to discover that future Hall of Famers tended to do pretty well in their minor league career! Who knew? But not all of these amazing prospects went on to legendary careers. We’ll find journeyman, role players, guys who never quite lived up to their young promise and guys who fit squarely in the “huh, I kinda remember him” category in the dust closet of our minds.

So buckle up for a fun trip through the back alleys of Giants minor league history. I’m going to try to spotlight one bright shining season for one guy who made it and one guy who didn’t at every position (though some positions will have a surplus!), build a starting roster for both and a stacked bench.

Today I’m going to start by looking at the Catchers — which is a particularly block-headed decision because, let me tell you, there aren’t a lot of great season in Giants history from the 2-spot!

Why Didn’t That Guy Make It?

Starting C

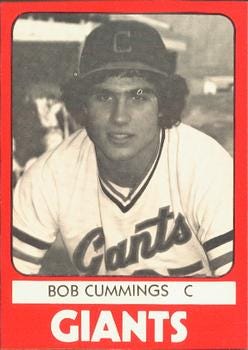

Bob Cummings, 1980, Clinton Giants (Midwest League - A), 19 years old

.282/.392/.447 13 HR, 18 SB, 67 BB, 62 K in 443 PA

1980 TCMA Clinton Giants collection

Writing about Joey Bart in a recent post, I noted the spectacular success the Giants have had with top 5 overall picks in the draft. While that is definitely true, that success falls off a cliff after the #5 pick, as the Giants have definitely left value on the table with their picks at the 6-9 overall spot.

Ah yes, the [Ted] Barnicle on the ship of Giants history! Oh Alan Cockrell, we hardly knew ye. I want you to move on past the ill-fated LeMaster (who’s taken far more abuse from Giants fans than the poor man deserves), past Steve Soderstrom whose son may yet redeem his Giants history (Legacy Pick!). And even past the shining light of this list (who still may bring bile to your throat). There, yes…stop there. The 7th overall pick in the 1978 draft: a 17 year old Catcher out of Chicago named Bob Cummings.

With a few decades worth of draft history to look back on, we know now that High School Catchers have probably the worst development history of any profile you can take in the draft. Check out the full list of 1st round picks . Not without its successes of course, there’s one newly enshrined Hall of Famer in that group, and a couple others who could be. But the full history of the phylum is pretty dreadful — ESPECIALLY when the pick is based on the player’s defensive abilities, as it appears the Cummings pick was.

The winter after his pro debut (hitting .234 with a .645 OPS in Rookie League Great Falls), Cummings won raves at the Giants winter instructional league. Though at the time, manager Hank Sauer noted:

“We have to be a little more patient with Bob because he’s such a green kid. He’s from Illinois and didn’t get that much baseball exposure as a kid. But our scout’s saw a lot of potential in him as a Catcher.”

One wonders if one of those scouts might have been Tom Haller — also a Catcher who came out of the Illinois High School ranks, and on the verge of taking over as the Director of the Giants farm system.

Regardless, patience with the youngster was frankly not on display the following season, when the Giants promoted Cummings from the Midwest League to fill in at AA while Jeff Ransom recovered from a broken finger. Cummings had been struggling in A ball where he was hitting just .207 with a .245 SLG — and the quick jaunt up to AA for a month likely didn’t help the struggles he was having adjusting to pro ball. Following that they sent the youngster to the Cal League rather than returning him where he had started. The peripatetic season did the 18 year old no favors, and he combined to post just a .552 OPS over the three levels.

But in 1980, as a 19 year old returning to the Midwest League, he put together the kind of season the Giants were hoping for. The power started to come as he slugged 13 home runs (he had just 2 total in his previous season and a half) and he showed excellent control of the strike zone (spoiler: we’re going to see a LOT of great plate control from prospects who didn’t advance to the majors as we look through history. There’s no way of knowing from this late date whether these walk rates against low-level competition had any meaning at all, or if a more Money Ball attitude towards OBP would have changed some careers).

This was the only season in which Cummings had more walks than strikeouts, but he always posted strong walk rates, finishing his career with an OBP nearly 100 points higher than his batting average (.258/.351). Once again though, patience might have been lacking as they pushed the 20 year old right back up to AA the following season. And there once again, he foundered, hitting just .228/.268/.332 with only 4 HRs and just 12 BBs in 254 PA (by far his worst mark on that front). Though that line would improve a little over the coming years, he’d never escape AA, playing six straight years at the level (he did appear in 2 games in AAA in 1985). In the winter of 1982, the former 1st rounder was dropped from the Giants 40-man roster to make room for a switch-hitting OF who had hit .308 in Phoenix and who would go on to be a member of two World Champion teams in Minnesota — former Fresno Stater Dan Gladden.

There’s no great mystery to why Bob Cummings didn’t make it — he may have had the arm and the hands to catch but the bat just never quite caught up. That’s a story that has a lot of chapters.

On the Bench:

Wayne Cato, 1976 Cedar Rapids Giants (Midwest League - A), 23 years old

.308/.371/.449 8 HR, 30 BB, 29 K in 397 PA

Cato was the opposite of Cummings in nearly every way — undrafted out of the University of Texas-Pan Am, Cato signed on with the Giants and for two years dominated low level play. He hit .372 in short-season rookie ball for the Great Falls Giants, making the league’s post-season All-League Team. He topped that by being the Midwest League MVP in 1976 while leading the Giants to a division title (they lost in the league championships).

Cato was always old for his level however, and never hit for much power. The batting average came down as he moved up, and his career would end just two years later after his ‘78 season in AA. Cato does have one connection with Cummings however: after his playing career ended he stayed on in the Giants system as a manager for three years. He’d mentor the young Cummings for two years as manager in 1979 and 1980 in Great Falls and Clinton.

Future Big Leaguer

Starting C

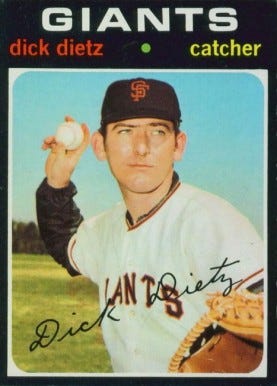

Dick Dietz, 1961 El Paso (Sophomore League - D), 19 years old

.332/.551/.652, 21 doubles, 24 HR, 94 RBI, 159 BB, 89 K

1971 Tops Card #545

In some respects, the Dick Dietz’ time with the Giants traced the history of Horace Stoneham’s finances. Did you know that the Giants were once considered one of the spending profligates of baseball? In the days of the “bonus babies” Stoneham — no doubt expecting windfalls to result from the move west to San Francisco — was one of the biggest spenders on amateur talent in the game.

An April, 1962 article in The Sporting News sounded practically agog in detailing the contracts being handed out by the Giants: there was Dietz and fellow Catching prospect Randy Hundley (both inked for a jaw-dropping $90,000), powerful SS Cap Peterson (we’ll see him in a later installment) and significantly less powerful SS Hal Lanier (both $75,000), as well as Gaylord Perry ($70,000) Ron Herbel ($60,000), hitting prodigy “Jimmy” Hart ($55,000), two more Catchers in Tom Haller and John Orsino ($40,000 apiece) and more. All that spending would culminate in the Giants’ record $150,000 handed out in 1962 to University of Santa Clara’s College World Series’ star left-hander, Bob Garibaldi.

By 1972, however, Stoneham’s fortunes were decidedly trending downwards. He was having trouble keeping the financial ship afloat, and was reportedly enraged by Dietz’ role in the 1972 players’ strike (Dietz was, by then, the Giants union representative and an active member of the union’s braintrust). The strike wasn’t long but it damaged the Giants’ ticket sales coming off a division winning season — and some hold that Stoneham simply gave away his All Star Catcher out of spite when it was over.

In between that alpha and omega, though, there was a long slow climb for Dietz who would spend most of seven seasons in the minors — as The Sporting News would often note, a much slower climb than a team might expect for $90 grand. Unlike Bob Cummings, the trouble for Dietz was never the bat — he hit everywhere he went. It was his stiff receiving that prolonged his minor league career. Dietz’ plethora of passed balls dented backstops everywhere he played — an issue he never overcame. He led the NL in passed balls his final two years in San Francisco.

It didn’t help any that he was often teammates with fellow bonus baby and defensive whiz Hundley. At one point, the Giants moved Dietz to the OF so that Hundley could develop unhindered by splitting playing time behind the dish. And considering Dietz responded with a career high 35 HRs and an 1.121 OPS that season, and that he admitted liking OF better because his took his mind off his defensive woes, it’s possible they should have left him out there. Maybe then they wouldn’t have had the worst production in the National League out of RF from 1964-68.

[As an aside, Hundley was dispatched from the organization in a minor, forgotten but absolutely wretched deal. The Giants sent a perfectly fine Catcher (Hundley averaged 3 Wins a season from 1966-1969 and was a decent backup through most of the 70s) along with starting Pitcher Bill Hands who went on to win over 100 games for the Cubs and post a career ERA+ of 114. For that package they got 112 awful ABs from CF Don Landrum, who batted .186 and was soon released, and about 2.5 years of league average relief pitching from Lindy McDaniel. “The Truly Terrible Trades of Horace Stoneham” is a story somebody really needs to write some day. If you want to understand the fate of the ‘60s era Giants, check the transaction wire. They dropped quality major league players like so much loose change among the sofa cushions.]

But back to Dietz and his wondrous 1961 season. It should be noted that El Paso was a terrifically hitter-friendly environment. Dietz would return to El Paso in 1963 to post that 35 HR season referenced above (in the interim it had magically transformed from a D classification team in something called the Sophomore League to a AA team in the Texas League). And he had just the third highest HR total on his team that year (even the light hitting Hundley posted a career high 23 HRs). But hitter-friendly or not, Dietz’ age 19 season was a thing of beauty. One can only imagine Farhan Zaidi side-eyeing those incredible 159 walks and .551 OBP! Add in 50 XBH and on the paper this was absolutely a Bondsian effort from a teenaged Catcher. The two years in El Paso gave a skewed view of Dietz’ power, though he would his 41 homers over his two full-time starting years with the Giants. But his total control of the strike zone could not be in doubt. Over 7 years in the minors he posted a .435 OBP and walked almost exactly the same amount as he struck out (561 to 562). That part of his game did carry over into his big league career, where he posted a .390 career OBP, including an extraordinary .474 OBP in his final MLB season in Atlanta (helping him post a 154 wRC+ in part-time duty).

I remember as a kid being mystified by Dietz’ fate. Why was he gone so suddenly? How was it possible the Giants got nothing at all in return for him? What happened here? How did you go from All Star to gone that fast? Whether he was blackballed or not (and I would say the evidence inclines that he was) the $90,000 bonus baby was certainly a star-crossed player for the Giants. In today’s game he would have been lauded for his on base skills and likely respected (and protected) for his union work. But 50 years ago he was a player the Giants just never quite knew what to do with — always focussing on the things he couldn’t do and missing out on the things he did so well.

On the Bench:

Gary Alexander, 1975 Lafayette Drillers (AA), 22 years old

.329/.453/.604 24 doubles, 23 HR, 76 BB, 90 K in 428 PA

Lafayette was definitely not a hitter-friendly park. Alexander and his 19-year-old teammate Jack Clark were the only two players on the team to hit more than a dozen HRs that year (and both of them ended their ‘75 seasons in Candlestick). Alexander was one of the first “prospects” I really remember being aware of as a teenager, probably because of the big power year he’d had the season before in Fresno, where he’d been a Class A All Star. Alexander was a star hitter everywhere he went in the minors, ending his minor league career a .300/.400/.500 monster hitting backstop. But after his first serious taste of the big leagues — when he hit .303/.406/.496 in 51 games — the Giants sent him across the Bay as one of six players in the epic Vida Blue deal. Though Alexander would have a 7-year career in the majors including time as a starter in Cleveland, that deadly minor league power bat never showed up and he hit just .230 as a big leaguer, though with some power and walks that was nearly good enough for an average bat (98 wRC+).

Final Thoughts

There are a whole lot of smart baseball fans out there, creating amazing new ways to look at our game. Three that have really impressed me lately are these:

Seriously, dig into Matt’s twitter account to see the full roll-out of this system. It’s pretty incredible what he’s doing. I’ll be talking more with Matt in the near future.

And then there’s friend of blog Kyle Goings who’s been hard at work most of the winter creating his new metric, DIGS. Enjoy all three! This may be the closest we get to baseball this year!