So, let's talk about Joey Bart

Begin the retrospectives

This is the first post in a series that will look back at the 2020 season for most of the Giants rookie players.

With the 2020 season sadly, part-bitterly/part-hopefully concluded, it’s time to start looking back so we can look forward. Since we have no minor league season to retrospect, here at There R Giants we’ll stick to the rookies — or even the still to be rookies — and look into each of their seasons over the next few weeks.

Since there’s no use ignoring the elephant in the room, it makes sense to start out at the top of the prospect chart and examine Joey Bart’s introduction to the bigs. It went….well, how best to describe it…

Something like that, yes. Joey did oft-times look like there were things flying at him from all directions and he was having trouble processing it all.

In sizing everything up, it’s crucial to keep in mind the context here. As I wrote back during Summer Camp:

The reality of his situation was always going to be that he needed to be in a place that simply didn’t exist. While Farhan Zaidi insisted that the Alternate Site really was providing him with “meaningful at bats,” there can be no doubt that taking what amounts to live AB from the same small handful of teammates every day pales in comparison to the competition of facing a real opponent in front of real fans and playing for real stakes. Kyle Haines and his crew certainly did al they could to give glorified spring training maximum value, but that value must perforce be limited.

Adding to that factor was the black pit that was the Giants catching position (remember the Rob Brantly/Tyler Heineman combo that started the year). Once the team started playing its way into contention the Catcher’s position made its presence known as a real weak spot in the lineup. So Zaidi and GM Scott Harris were stuck in the unenviable position of needing to be patient with Bart while also knowing he likely was an upgrade that could help the team.

Again, as I wrote back in July:

Bart’s opening weekend was fabulous, fans were giddy!

But soon the reality of the situation began grinding those giddy giggles into nervous ticks.

The positive spin on the season was that Bart got a taste of what big league baseball really is, and has a better understanding of what he needs to work on and how much work is really involved in being a big league catcher. As Evan Longoria said on Sunday, having Buster Posey there to mentor him and share some of the load almost certainly would have made the difficult transition a little easier. For good reasons that wasn’t the case in 2020 but hopefully will be in 2021.

The less positive spin is that Bart really struggled as an offensive force, and while his relationship working with pitchers appeared to improve as the year went on (with the notable exception of Johnny Cueto) that was an area of difficulty as well. And it’s a small thing, but I don’t believe I’ve ever in my life seen a Catcher simply not catch pitches as often as balls popped out of Bart’s mitt this summer. Just catching big league stuff appeared to be a steep hill Bart struggled to surmount.

It certainly didn’t help things any, that the guy selected one pick after Bart, Philadelphia’s Alec Bohm, simply destroyed MLB’s Eastern Region to the tune of a .338/.400/.481 rookie year. Bohm had a little more experience to start the year, but could 160 additional plate appearances in AA really explain that difference in success? Or was it the huge and complex burden of catching that really accounts for that divide? Both? Neither? Something else entirely?

That’s sketching in the backdrop, but how about we dive into the real specifics of what went wrong — or as a “growth mentality” like Gabe Kapler’s would certainly view things, where there are opportunities for improvement.

It’s interesting to compare Bart to his partner, rookie Chadwick Tromp. By any measure, Tromp’s offensive campaign was no more successful than Bart’s. He struck out in nearly a third of his plate appearances. He posted a putrid .219 OBP. But Tromp showed the ability to do one thing Bart couldn’t — sit on the pitch he could whale on and whale on it when it came. Which explains his current 4 HR to none lead over Bart in their short careers.

Bart’s puzzling inability to get to his power this year would seem to have a pretty classic predicament at its heart: he was constantly between the fastball and the breaking ball. Soft-balled to death by breaking balls that he seemed capable of neither laying off nor making contact with, he couldn’t then catch up to heat.

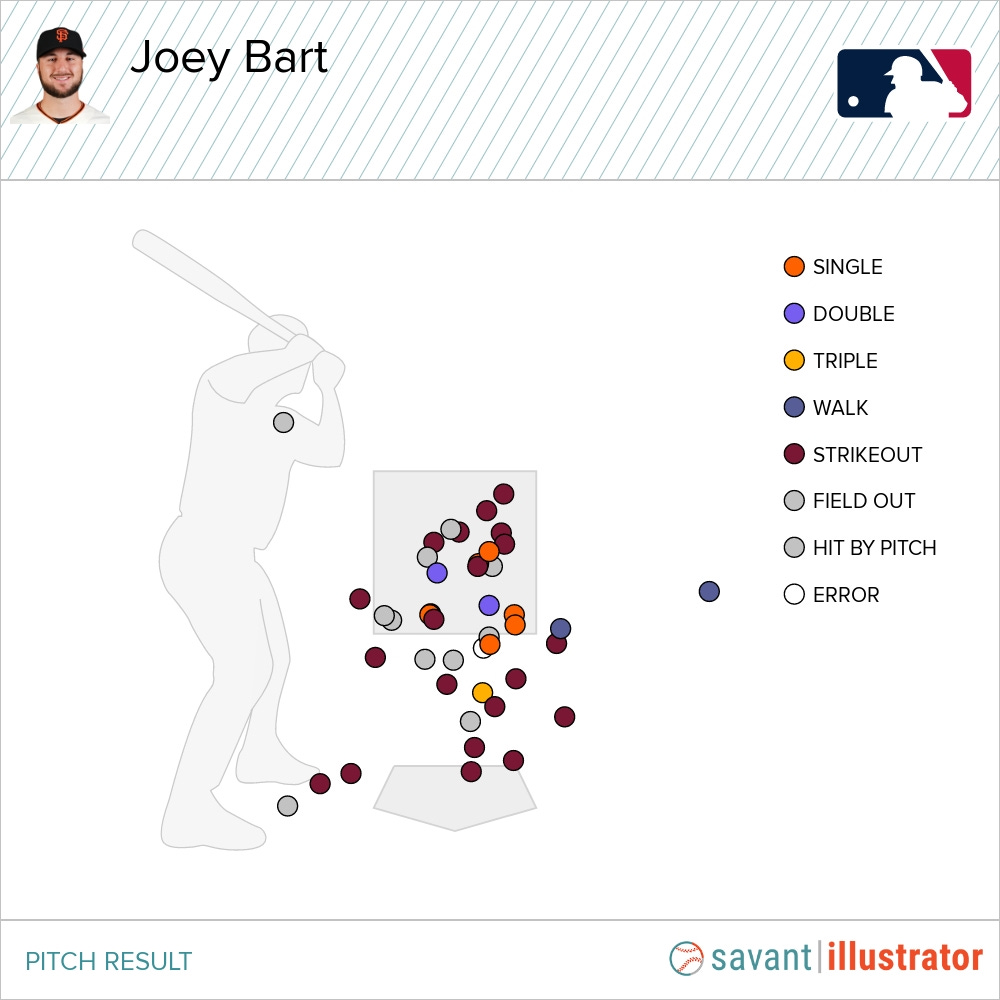

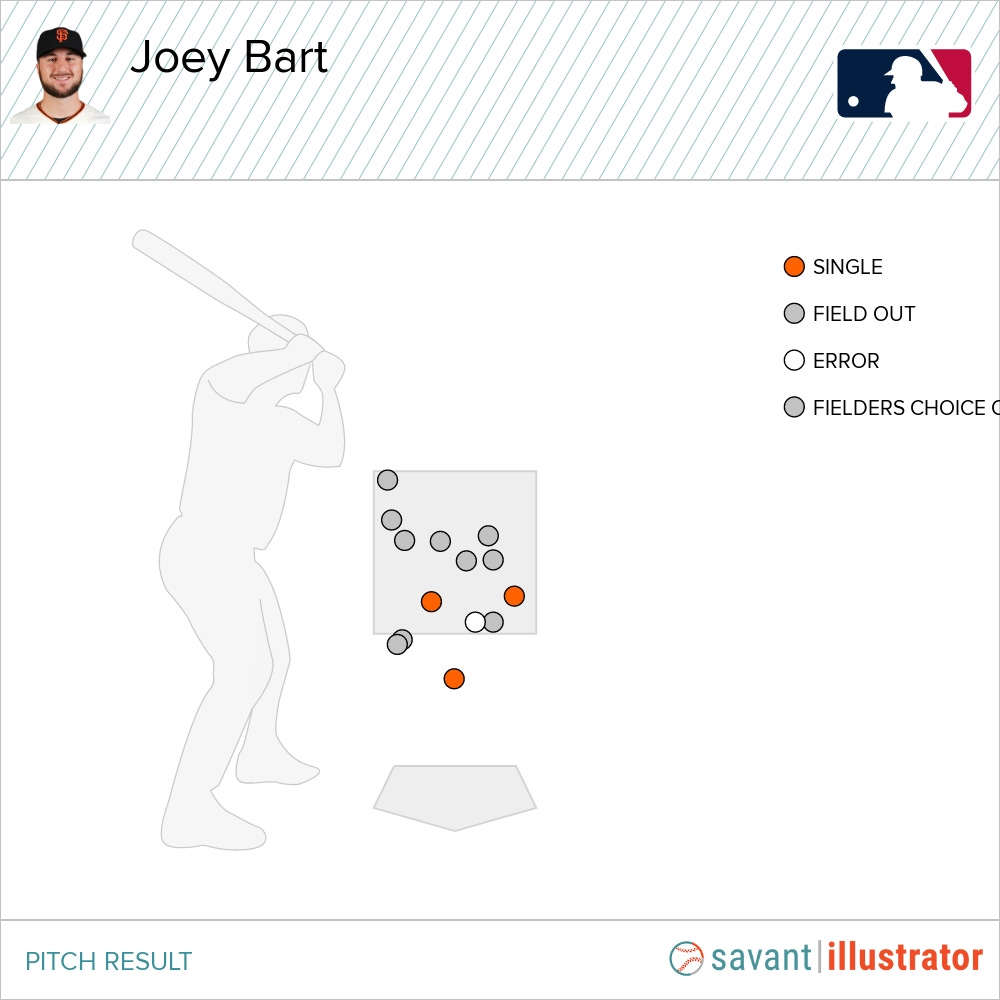

Let’s take a spin around Baseball Savant and see if we can illustrate the twin issues. Below are the results of at bats that ended on curves or sliders — we’ve read a lot about Bart’s 41 to 3 K to BB ratio this year. Well, here are half of those strikeouts.

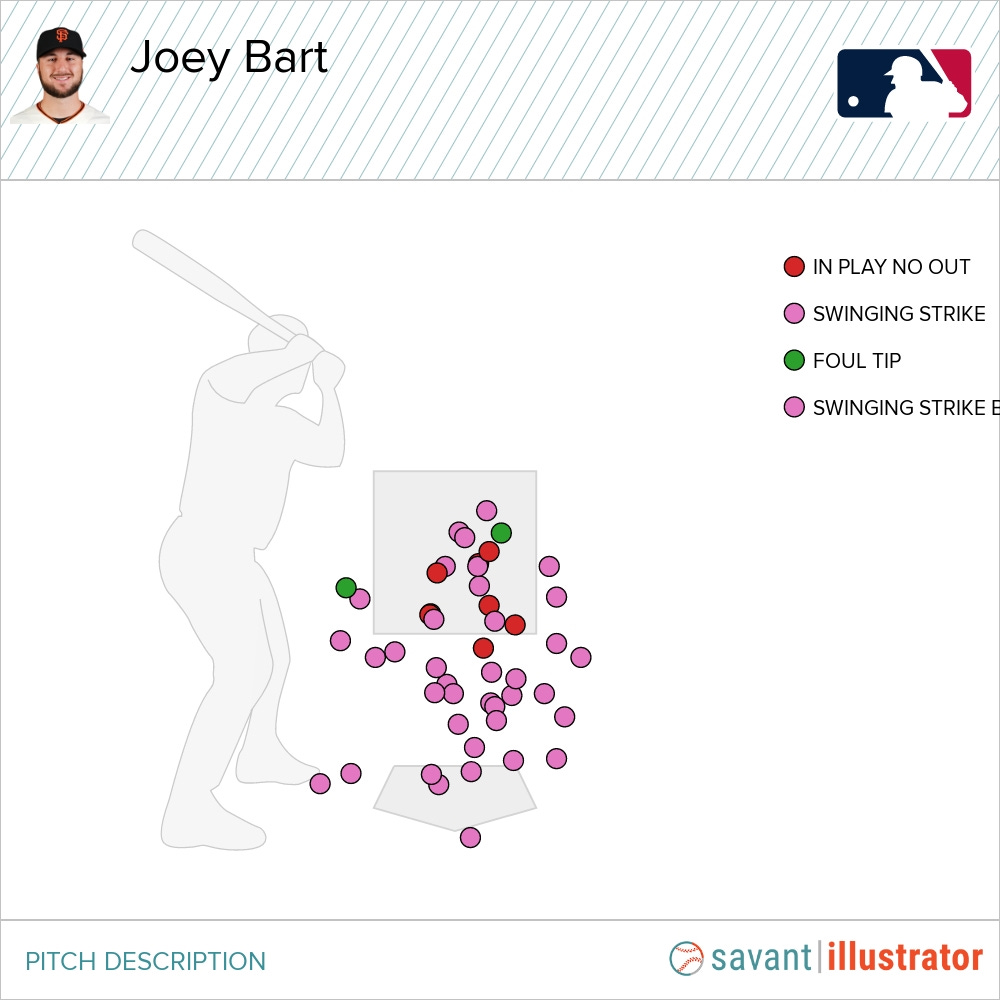

It’s quite evident from this graphic Joey was not constrained by the bounds of the strikezone when fishing after off-speed stuff. There was a hole lot of chasing at the shoe-tops going on here. If we don’t limit our view to just the final pitch of the at bat, and look all of his swing’s on breaking pitches, the problem becomes even more acute.

On Savant, you can hover over each of those dots and get full info on the pitch: date, inning, pitcher, exact velocity readings, etc. And if you hunt around in those dots enough you’ll notice examples of pitchers getting Bart to chase breaking balls below the zone multiple times within the same at bat. For whatever reason, Bart just didn’t seem to be seeing, recognizing, and processing big league spin (or perhaps understanding how much break was going to result).

This is a pretty big damn deal because it breaks the 1st Commandment of New Giants baseball:

Though Shall Not Commit Bad Swing Decisions

Indeed, it breaks it, trods on it, and then stomps on the broken remnants. The Giants hitting philosophy this year was for hitters to be aggressive on balls they could crush and passive on balls they couldn’t. Bart clearly failed that Philosophy course and it’s a big hurdle he’ll need to clear in order to get to his power in games. So growth opportunity #1: Recognize spin and lay off pitches darting below the zone.

But the second part of that philosophy was also somewhat problematic because it frankly wasn’t clear what pitches Bart really could do damage to. And that' leads us to Joey’s issues with fastballs this year.

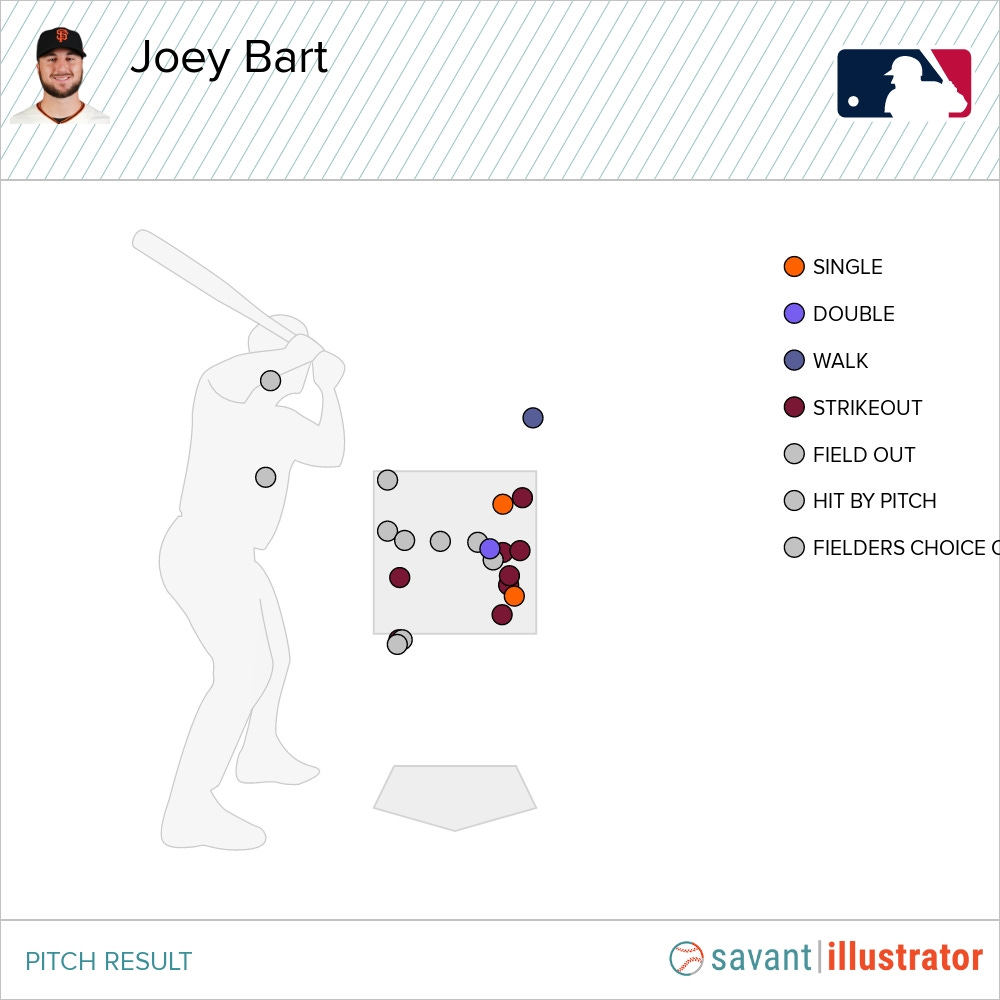

Here, now, are all of his plate appearance that ended in a fastball:

Once again, we have a lot of outs to deal with. In Bart’s first few days he was having success driving fastballs on the outer half of the plate. But pitchers quickly countered and started pounding him in (which was the minor league scouting report). Primarily pitchers were getting him to pound inside fastballs onto the ground — some were broken bat squibs, some were hit hard, but nearly all were outs because grounders aren’t Joey Bart’s friends. Increasingly, as he became conscious of that hole, pitchers became more successful on the outer half as well, where swing and misses started popping up (not all the brown dots on the outer half).

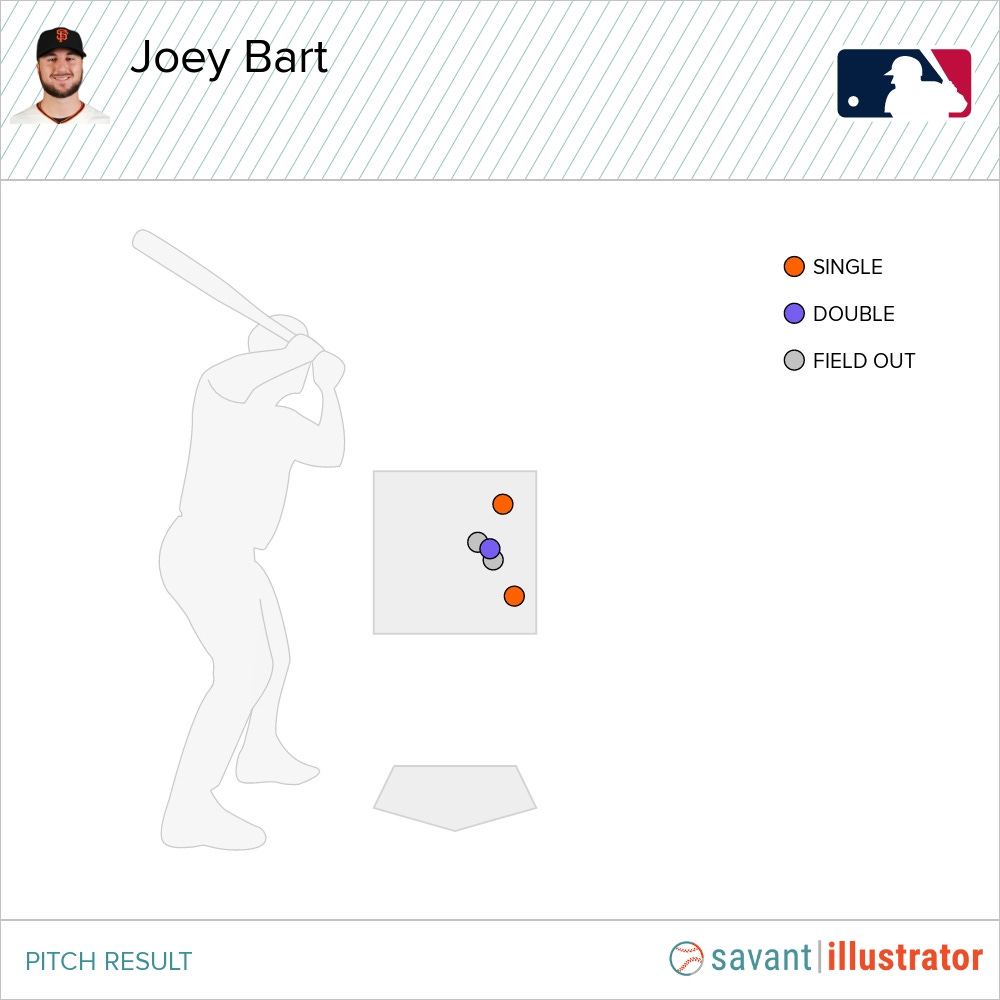

Breaking it down further, we can find two specific sub-issues Bart had with fastballs. First, he just wasn’t barreling up velocity. Here we see all of the fastballs thrown > 93 mph on which Bart produced an exit velocity >90 mph. Note: there are far fewer dots here!

Interestingly, all of those pitches which Bart hit hard were hit either the opposite way or up the middle. There wasn’t a single example this year of Bart squaring up velocity to his pull side. If we pushed the Exit Velocity envelope a bit higher, to say, over 95 mph EV, then we get down to just three pitches all year where he produced loud contact on a 93+ mph fastball. The triple he hit off the bricks against Robbie Ray in his first weekend. An RBI single smoked under the 1b glove against Chris Paddack last Friday night. And a flyout to the RF warning track in early September against Arizona.

Some of his most memorable hard hits of the year came instead, off of breaking balls that didn’t bite enough and stayed in the hitting zone:

If you’re wondering about Bart’s other triple — lined into Triple’s Alley against the Rox. That pitch was officially 92.6 mph so just below my arbitrarily chosen velocity line. Mentally add that one into the above chart if you so desire.

The second problem is that Bart somewhat surprisingly produced little to no loft in his swing this year, pummeling one ball after another into the turf. A launch angle <10° results in a ground ball and below we see all the fastballs Bart put in play at that launch angle this year:

Bart has had periods in the minors where his groundball rate spiked — particularly last year when returning from his broken hand.

But over the final six weeks of 2019 he had shown real improvement in that area, especially during his time in AA and the Arizona Fall League. But that improvement evaporated with the head-spinning transition to MLB pitchers. There was some chatter from amateur swing-diagnosticians on the internet that Bart’s swing developed a chopping down motion this year, perhaps in attempt to fend off pitcher’s attacks on his inner half. Perhaps he simply became so breaking-ball conscious that he couldn’t time up harder stuff.

Regardless, the 2020 season turned into an experiential enumeration of development priorities. The pitchers of the National and American League Wests kindly demonstrated to Joey all of the flaws in his game that he might want to look into. “Oh did you know you have a hole here?” “And a hole here?” “You really need to get this pitch in the air more!” “Oh, and you chase this pitch far too much, young lad!” “No problem, happy to help!”

As a result, there’s an easily identifiable tangle of weaknesses in both approach and mechanics that Bart and his coaches will need to tackle this winter, next year and beyond:

Better recognition of spin

Cover the inner half

Identify the pitch/zone he can damage and focus on it

Produce more Loft in swing

That’s not an ambitious “To Do” list or anything, is it? Oh, and did we mention the constant pitcher meetings and learning how to lead his staff and comprehend scouting reports for all opposing hitters, and call games and read hitter’s swings, and master changing signals, and improve the framing and catching skills on big league movement? Yeah, that’s a laundry list. And every single item on it can grind a strong man to a pulp. It’s going to be a climb.

Fortunately, 2021 should see the return of our Buster and Joey should be able to head to Sacramento to work on these things away from the maddening crowds (if the minor leagues exist next year — but that’s a different story). When the time is right, he’ll have one of the greatest for a mentor when he returns to San Francisco.

For the Giants and Bart, the 2020 season was always likely to be the Kobayashi Maru. There was just no way to win this simulation. But they made it out alive and the gift of it is they know clearly now what work must be done to conquer the next test that comes.

If you liked this There R Giants post, why not share or subscribe?

Why does he have to play catcher? If we trade Longoria or Belt for pitching, could Bart play 1B or 3B and spend most of his time focused on becoming a better hitter and not have to worry about being a catcher, as well? #patrickbailey

Any day you can throw a Star Trek reference into a player eval is a good day. ;-)