Spreading the Money Around

Does the newest international class tell us anything about Giants' tendencies

Today is the day! Contracts will abound and we should be seeing plenty of pictures of happy looking 16 year olds inking their deals alongside frumpy looking older scouts, all in Giants gear with a Giants’ banner behind them. A lot of those happy smiles should be familiar to you from Wednesday’s post, but I want to go back to my introduction to that piece and expand on a key point I mentioned in passing on Wednesday:

In 2018, the Giants jump-started their system by spending almost $4.5 million on three players (Marco Luciano, Jairo Pomares, Luis Matos)… However, in the two years since, they’ve taken an approach of spreading their bonus pool around more evenly, casting a wider net looking for talent.

There’s no doubt that the last two classes have diverged significantly from the epic 2018 class in terms of distribution of bonuses.

For Giants fans who are getting hyped on Luciano-Matos juice lately, that might seem something of a bummer. “Hey, make with the superstars already!” you might be shouting. “Where’s my annual Luciano-fest?” And it’s a reasonable question. As old friend Grant Brisbee noted just yesterday, it’s our sports-giving right to demand high-rolling salaries and headline acquisitions.

And in the international market, keeping an eye on how teams are distributing their bonuses makes sense. As McDaniel and Longenhagen wrote in Future Value:

The investment posture of the international department, across dozens of decisions every week, has to lean, at some level, into one of these two camps. Is the organizing principle of decision-making a fear of making a mistake (and staying out of the top of the market) or trying to find impact talent wherever it is (and responsibly seeking risk in search or reward. — Future Value, p. 96

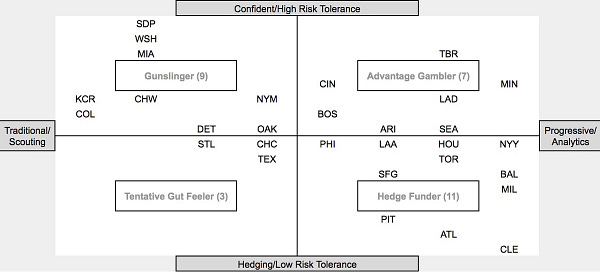

And given that McDaniel has placed the Giants current front office in a group with the teams who fit in the former of those two camps, this is a trend that bears keeping an eye on. Are the Giants really one of the “Hedge Funders” of baseball, as McDaniel’s survey of the industry suggests?

It’s still far from clear. There are arguments you could make to the contrary. As Ben Badler and I discussed last summer, because of the long lead times on international classes — where commitments are essentially forged when players are 14 or 15 — it’s a lot harder to draw a bright line between the acts of the current administration and the former. The top player in this year’s market, Cristian Hernandez, almost certainly had agreed to a deal with the Cubs while Scott Harris was still in Chicagoland, after all.

And given that the current International Scouting Director, Joe Salermo, has also the guy who approved deals for Luciano and friends, facts seem to favor the idea that there’s more continuity of approach than a shift. As Badler says, there just aren’t all that many 13 or 14 year olds who jump out at you in a given class and force you to start writing $3 million dollar checks.

There’s also the fact that the Giants’ history of shopping at the top of the international market is more tragedy than triumph. The 2006 J2 class was, as it turned out, filled to the brim with huge value signings. Jose Altuve practically begged the Astros for his $15,000 deal (they rejected him after his first tryout). Sal Perez, Cesar Hernandez, Freddy Galvis, Danny Salazar, Jean Segura, Alex Colome, heck even newly-minted millionaire Liam Hendricks were all signed that year for minor investments — most of those guys at just five figures. The Giants, meanwhile, topped the market giving out their largest amateur signing bonus ever at the time to Angel Villalona ($2.1 million).

A decade later the J2 market poured forth superstar talent — Juan Soto, Fernando Tatis, Jr., Yordan Alvarez, Vladimir Guerrero, Jr. And, with prospects like Cristian Pache and Jazz Chisholm just arriving in the majors, there could be even more stars from this group. Unlike the 2006 class, these guys weren’t the small fry/big success stories, they were the known top of the class commodities. Still, Tatis signed for just $700,000, and even Soto was had for $1.5 million. The Giants topped the market with the largest international amateur bonus ever when they gave $6 million to Lucius Fox, who is now on his third organization. Arguably, that was the year to go whole hog and sign everybody they could get their hands on once they were already well into the penalty box, but the Giants chose to put all their chips in the Fox box and it cost them — the next three years they couldn’t sign a bonus higher than $300,000.

And, of course, what they found in those three years is that they were still capable of finding exciting talent without the million dollar price tags: Alexander Canario for $60,000, Luis Toribio for $300,000. There’s plenty of value to be found in this market at every price point.

From the International Market to the Draft

Still, what’s interesting to me about these last two signing classes is the way they appear to connect to everything the Giants are doing throughout their departments. Spreading money around evenly doesn’t just apply to their international classes.

It’s also the approach they’ve taken to the draft in the last two years. In both 2019 and 2020, they’ve saved money in the first round by signing their top pick to a below-slot deal and then used their savings to get some above-slot deals later on. To give you an idea of how different teams use their bonus slots in drafts, let’s look at a couple of examples from 2019 (the last full draft).

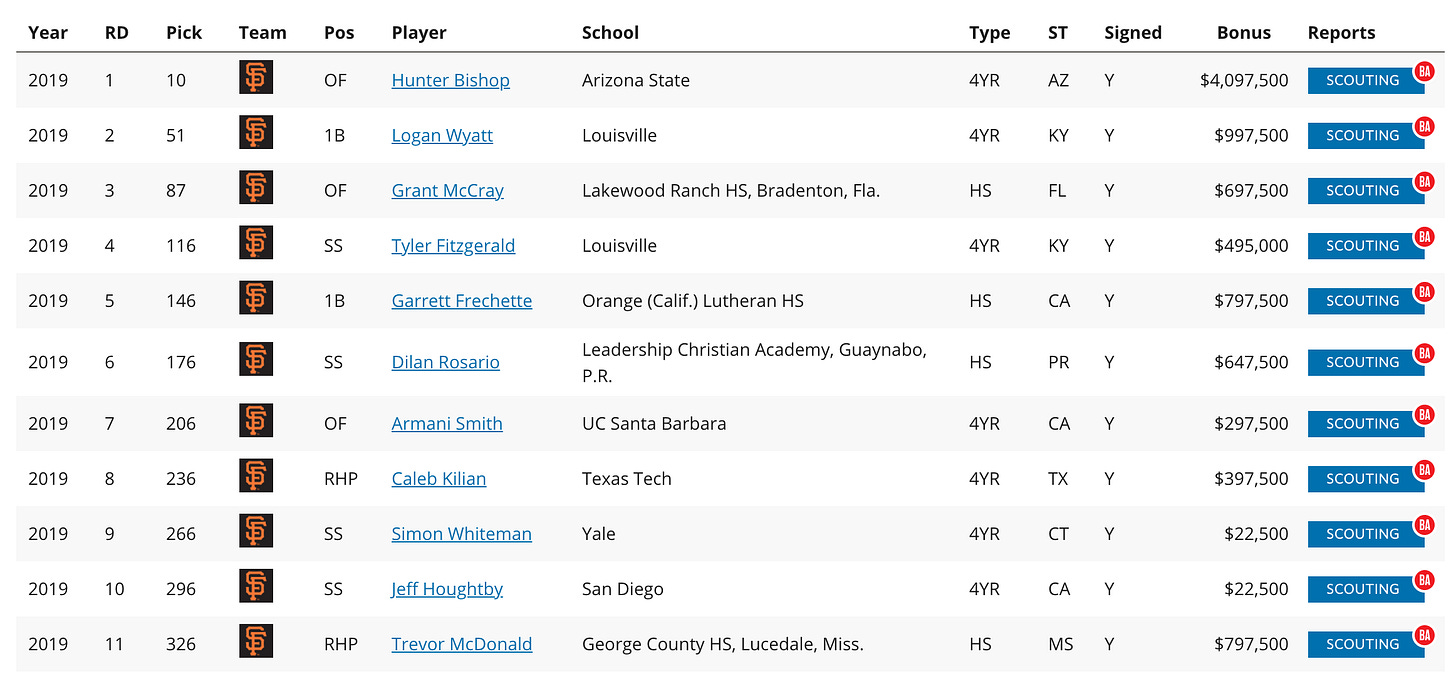

Here’s the way the Giants used their bonus pool in the 2019 draft:

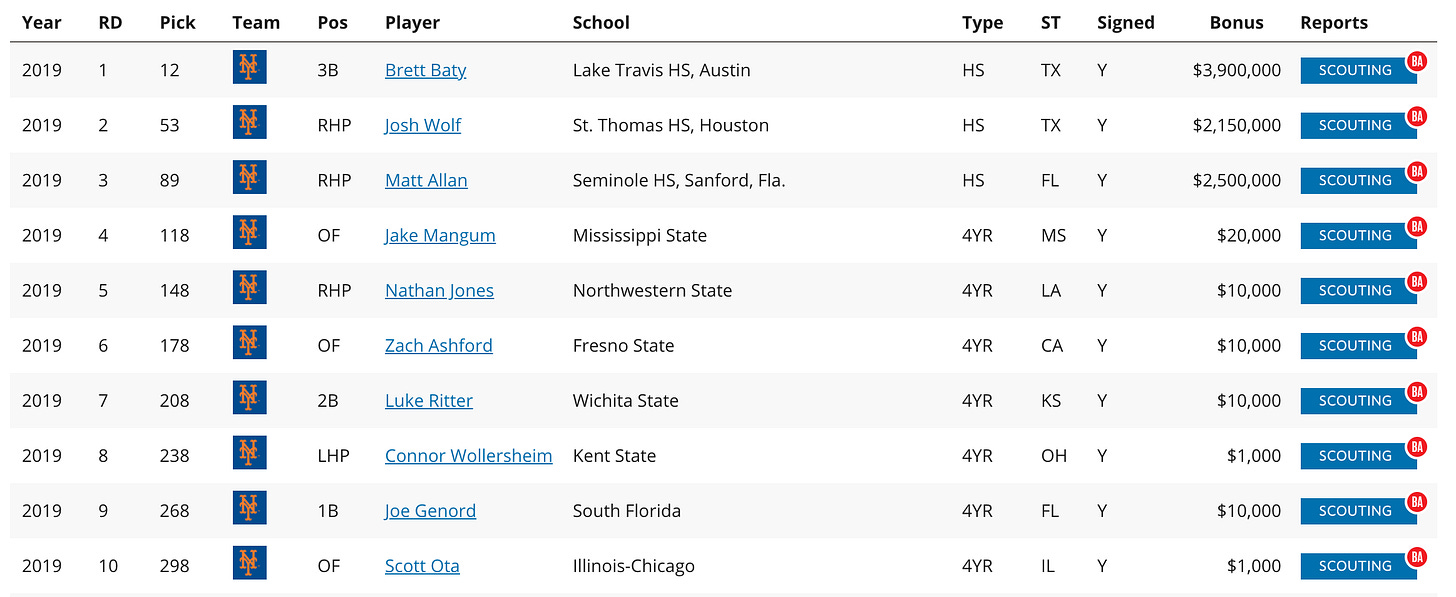

Here’s the NY Mets 2019 draft:

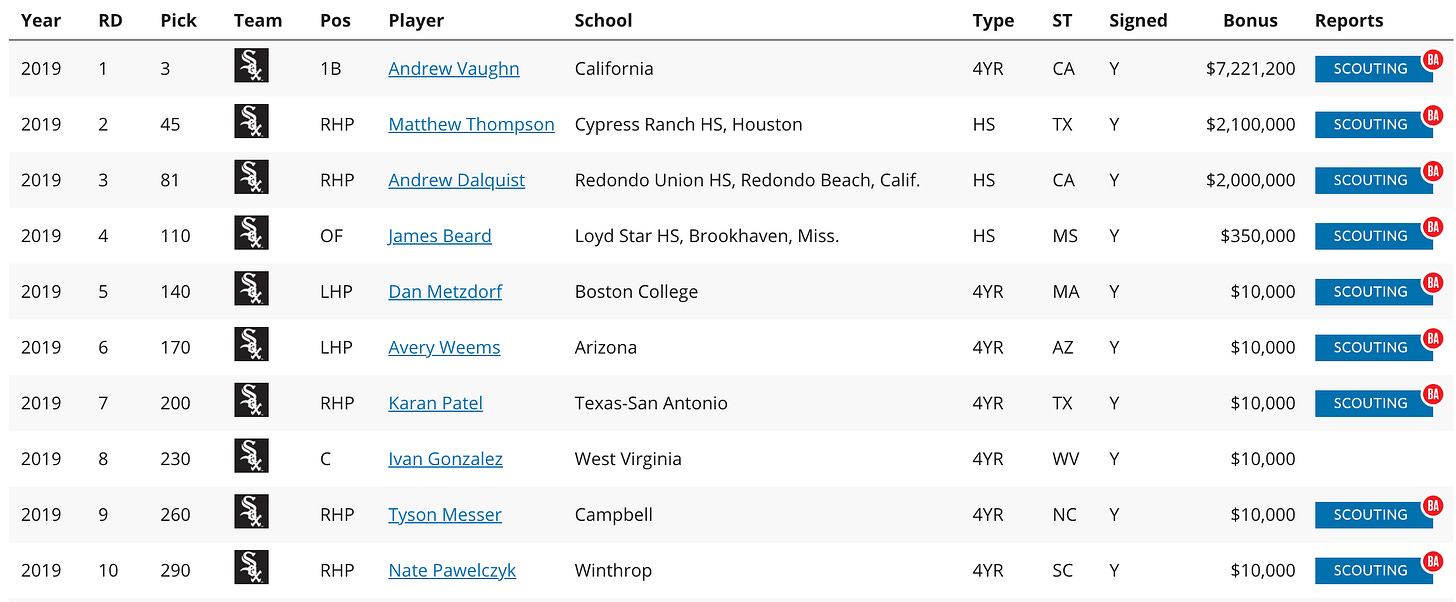

or, say, the Chicago White Sox:

See the difference? The Giants signed several more players to overslot deals over the course of the draft — six players in all got more than their slot value. But no one got $1 million more than their slot, as the White Sox gave 3rd round pick Andrew Dalquist (slot value $755,000), not to mention the near $2 million overslot that the Mets gave Matt Allen (slot value $668,000). The Mets and White Sox strategy was to “spend out” on a couple of players they judged to be spectacular and then drop immediately to the senior sign/org player level of the draft effectively punting on most of their rounds in order to get the talent they wanted.

The Giants, instead, spread their risk out, bringing in a collection of high school talent (Grant McCray, Garrett Frechette, Dilan Rosario, Trevor McDonald) rather than putting all their eggs in one Matt Allen-shaped basket.

You might be thinking, “ah, but Kyle Harrison!” And that’s a great retort! Harrison was bought out of his UCLA commitment with an overslot deal of about $1.8 million. And that may, indeed, tell us that the Giants are being strategic about their big spends — that their scouts viewed Harrison in the same light they did Marco Luciano, or in a very different market, Bryce Harper, as the exception that proved the rule. But it is difficult to know how to read intentions in the truncated 2020 draft where the choice to spread money around was limited to begin with by the relatively few picks that each team had. Even with the large overslot deal to Harrison and a much more modest overslot deal to Nick Swiney, the Giants ended up handing out seven-figure deals to four of their seven picks with a fairly even distribution.

Because every team is dealing with differences in number of picks and bonus pool money, it’s difficult to make too many broad statements about draft strategy. But the Giants seem to be staking out a strategy of looking for underslot talent with their first pick — a strategy that could have been a decisive factor in their selection of Patrick Bailey over Turlock High School catcher Tyler Soderstrom, for instance. Though the two catchers ended up signing for similar bonuses ($3.7m for Bailey, $3.3m for Soderstrom), Bailey’s deal with the Giants was $400,000 underslot while Soderstrom’s was about $700,000 overslot at the 26th pick. If Soderstrom’s agents were looking for slot or above at the Giants’ #14 pick, it’s entirely possible that that might have pushed them in a different direction, where they’d have more money to spread around a bit further. And, of course, it’ll be years before we can make a direct comparison of how that hypothetical decision turned out.

It’s important to note that this isn’t about “being cheap” or not spending money. The Giants have spent money in significant and important ways — buying a free 1st round pick in Will Wilson, paying to roster a second full Instructional League team and expanding their presence in the rookie complex leagues (AZL and DSL). Rather, this is about the philosophy of how to spend money most efficiently and effectively.

What Does It All Mean?

It’s dangerous to try to connect too many dots into too sophisticated of a pattern. The Giants, like all teams, are broken down into different departments, each responding to broadly disparate circumstances. And, as I noted above, there are enough contra-examples (Harrison, Harper) to suggest that the organization isn’t being too strict in adherence of any one ideology.

But as so much of the debate around the organization starts to focus on when and how they will “spend big,” the question is definitely worth asking: how risk tolerant will this front office be when it comes to major commitments?

Are they being strategically tactical and waiting for the perfect moment to spring — whether that spring comes in the form of the $4 million dollar J2 signing or a nine figure deal to the top of the free agent market?

Or is spreading risk (read: money) around, woven deeply enough into their organizational DNA that they’ll tend to shy away from the top of most any market? Are they a club that will prefer, as Kerry Crowley recently speculated, “to use the money they’d need to sign an ace and spread it out to three or four quality starters in future off-seasons.” That’s the type of thinking that has typified Cleveland’s front office, making small moves that maximize how long a window can stay half open, as opposed to big moves that try to get it fully open for a shorter period of time.

With the 2021 off-season beginning to loom large in fans minds (especially those fans who love a big marquee signing to light their winter fire), the question of how the Giants approach that market will get increasingly louder throughout the coming year (especially if a playoff-berth fades beyond the horizon during the course of the summer). Is the time coming when the Giants will begin to tactically make some bold moves, or are they inherently a club that tends to prefer three $10 million players over one $30 million player, spreading the risk around to fill the most needs?

If connecting dots is your thing, perhaps today is one more tiny data point pointing in the latter direction. Not a big one, maybe not a significant one. We’re still waiting for the day when the new Giants will sign their Marco Luciano.

But while we wait, it’s worth considering that money isn’t the only resource for talent acquisition. Traditionally, the thought has been that you pay for tools and develop skills. While both vehicles are complicated and rife with failure, throwing money at an issue is, at least, relatively straight-forward and it’s always been considered a necessity: tools play in the major leagues while skills can often have a AA shelf-life.

One reasons why teams like Cleveland — and perhaps San Francisco — shy away from spending at the top of markets is their belief that they can tweak that formula by gaining a competitive advantage in development. The Giants clearly have this belief, at least, in the major league market. As Scott Harris told the Chronicle’s John Shea this week, the team believes it has the “pitching infrastructure” to get quality production out of the lower tiers of the free agent market. Inside that infrastructure, we can presume, they are developing information systems, technology, statistical models, teaching methods — all of which they believe can, to some degree, replace or temper money as a needed resource for talent acquisition.

It’s likely the Giants have the same belief about their growing prospect development system. Spreading the money around on several “bites at the apple” makes sense if you are convicted in your belief that you can get the star talent out of a Grant McCray or Garrett Frechette-type talent, given enough chances. That’s the essence of diversifying risk: take your chances on developing one or more of four solid talents rather than spending the bulk of the money on one talent, judged to be spectacular.

As is always the case in baseball, the proofs to the theorem will work themselves out on the field of play.

Q.E.D