It’s an enduring regret of my baseball fandom that I’ve never come away with a ball hit into the stands. Mostly, I’ve never even come close to one — never close enough to give a lazy half-hearted raise of the hand or hunch up in my seat ready to stand and grab. My closest ever experience with a foul ball, however, was one I remember not with regret but with a faint trace of terror.

We were sitting right on the rail down the 3b line at the ‘Stick one day, when Dave Kingman got his long arms out in front of a pitch and clocked a foul screamer directly at my brothers and me. Barely thinking to react at all, the liner was inches away when it clanged off the rail with a gong that would call cattle home from a mountainside, careened out to CF with the arc of a high fly ball, and, if I’m not mistaken, shifted the entire footprint of Candlestick Park 5° towards Brisbane.

That memory impressed on me very early on the awesome power-generating force of a Very Large Human™. And I dredge this memory up today because the Giants happen to have just such a Very Large Human™ applying his power-generating force in the lower reaches of the minor league system.

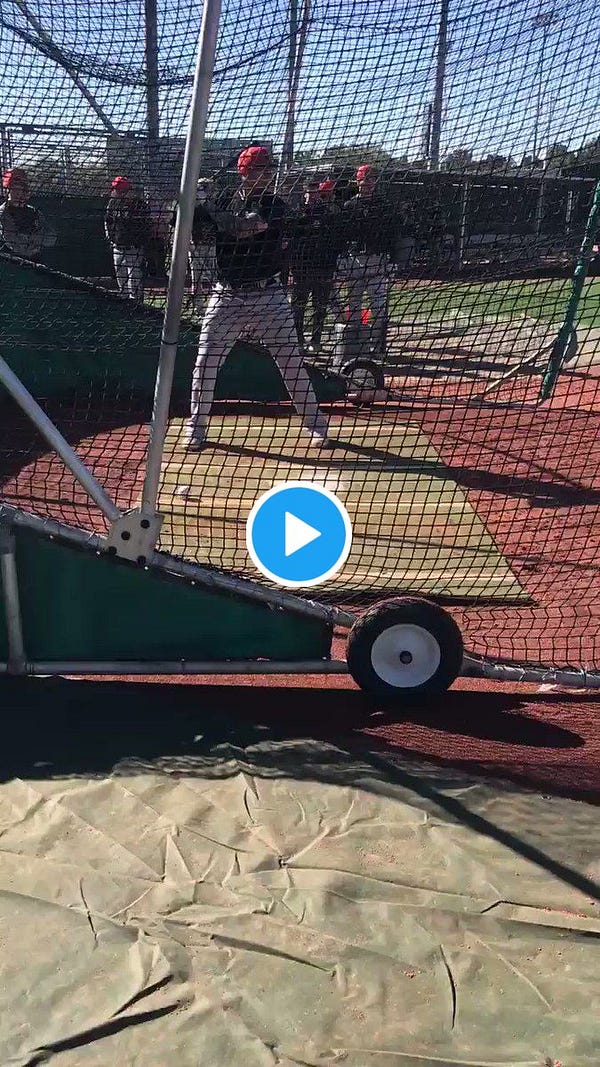

The aptly-named Connor Cannon is indeed capable of launching a fusillade of awe-inspiring shots during a BP session. An enterprising minor league team could do worse for a 4th of July promotion than to have him take batting practice in front of live symphony performing the 1812 Overture. With nearly every aspect of the game quantified at this point, there’s little room for legend anymore, but, during Cannon’s career at UC Riverside, his home runs were the stuff of legend among the scouts who covered him and compared stories of how far they’d seen Cannon hit a baseball. My friend Jason Pennini (now a scout for the Minnesota Twins) once memorably wrote of Cannon: “[he] is best described with three flexing bicep emojis.”

I use a lot of video in these posts, and I never stop to note that video is, in essential ways, a particularly unsatisfying vehicle for appreciating the physical world. Cameras spread a veneer of normality over everything. The cognitive dissonance of life bent out of scale is missing — centered away by our standard sense of framing. An athlete speeding past competitors, as seen through the centered-up perspective provided by incredibly talented professional cameramen, could be Zeno’s Arrow, forever trapped in the illusion of motion. Seen live, the sensation of watching true speed is simply scintillating. Even prodigious power can seem paltry and meagre on video, which fails to capture the ball’s exploding arc into the sky at a speed that feels suddenly untethered from the physical realm around it. Our brains trip trying to process this Matrix-like fold in the fabric of reality, and an involuntary “ooohhh” of appreciation is pulled from within us.

The same thing is true of size — I say that Cannon is huge, but it’s hard to appreciate in a You Tube clip where he’s framed up in basically the same way anyone else would be (just enough head room, face just left of center). But in person he’s mammoth — 6’5” and every inch of it, listed at 240 lbs of chiseled granite (I suppose officially his body mass is just made up flesh and bone, like the rest of us). With the classic “long levers” of a tall, lean hitter, Cannon generates just massive loft and backspin. He shows easy double plus power even to the opposite field — right-center field is a frequent target of his missiles. By the time Cannon was done at Riverside, he’d set both the season (16) and career (34) records for home runs. The apogee of his career came near the end of his junior year when he personally ruined UC Santa Barbara’s chance of hosting a College World Series Super Regional, launching four home runs in a weekend series against the #9 team in the country. In the finale of the three game series, he homered twice off the Gauchos ace Ben Brecht (taken in the 5th round by Tampa Bay) to clinch the series. You can see video of those in the clip below, both of which were sent out to the opposite field.

In all honesty, I probably should have included Cannon in last Monday’s post when I talked about the contact-challenged power hitters in the system, but I wanted to keep him for his own post. The general consensus of scouts during his college career was that he generally kept his swing-and-miss in check given how long his arms were. But he did strike out 25% of the time at Riverside and he continued that rate in his pro debut in the rookie league AZL. Given that he was old for the league, that level of whiff was certainly noticeable.

But that shouldn’t obscure the other numbers he produced at the level — a 1.088 OPS, 13 HRs (he looked to be making a run at Joey Gallo’s league record before a promotion to Salem-Keizer), and a .400 OBP. What trouble Cannon has with contact doesn’t come from a poor approach or lack of selectivity. As you can hear him discussing in the above clip, he has an idea at the plate — he goes up hunting fastballs to launch. He walks about 8% of the time and, as the Giants instructors work with him to identify what he’s trying to do, one can imagine that number going up.

In many ways, Cannon seems like the ideal player type to adopt the organization’s new mantra: crush it or let it go. Accept strikeouts as the cost of doing business, take walks when pitchers avoid you, and when you do swing, crush the pitcher's will to live as much as you do the baseball. Obviously, as he develops, Cannon will need to find ways to defend the inner half of the plate, as all pitchers will see a man of his size and immediately try to bust him in to avoid allowing him to extend the arms. I don’t want to oversimplify that challenge, as we saw with Joey Bart last year, it’s an incredibly difficult thing for a big player with long arms to get a short swing to the inner half. But, still, there’s a path to success for Cannon if he can simply keep hunting fastballs and bashing them into a fine, powdery mist.

“This all sounds pretty exciting,” you’re probably saying about now! “Why aren’t we hearing much more about this Very Large Human™?” Well, there are reasons! Scouting reasons! Many of which are good and solid and true — there is a decent amount of swing and miss, the track record comes against small school competition rather than a more competitive power conference, etc. But some of Cannon’s slight reputation falls into what I think is a small scouting blind spot that can encourages a player’s limitations to blot out his potential.

To start with, there’s the defense. While scouts might have told tall tales about his in-game home runs with glee, they also labeled him with a dismissive “DH-only” that can automatically knock a college guy down a few steps. There’s good reason for this — the game, particularly at the highest level, takes a tremendous amount of athleticism, and the player who looks like a DH at a small conference college feels unlikely to possess the athleticism needed to get that highest level.

Scouts, who watch hundreds of thousands of hours of baseball and see thousands of players, build up a mental-image data base in their brains of what bodies tend to produce successful outcomes — that’s how a player as splendidly talented as Jose Altuve, for instance, gets overlooked. Despite the continued demonstrated ability to hit, Altuve’s body just wasn’t one that had much precedence for successful outcomes in most scouts’ mental archives; so he got dinged for that. The same is true for a college “DH-only” player. You’re fighting uphill from the start because the demonstrated history of those players just hasn’t been great.

But, if you want the glass half full version, that’s exactly how a player like the Dodgers Edwin Rios got overlooked. Rios, like Cannon, went to a small college (Florida International), where he got a lot of reports that said something like: “mashes RHP, DH only.” He went in the 6th round, mashed his way from rookie ball to the majors in four years, and now is the proud possessor of a World’s Championship ring (yes, it really happened). All because the thing he could do (mash RHP) turned out to be more important than all the things he couldn’t do (basically, everything else). Of course, Rios has the advantage of being LH, and his college career speaks to a better ability to cover the zone and make contact, but his career isn’t so dissimilar from Cannon’s that you can’t look at them and imagine a parallel path.

It’s the path of the “one tool player.” Scouts don’t like a “one tool player” and again, for good reason. Players who have multiple ways to positively affect a team can create opportunities for themselves without getting a best possible outcome with their bat — guys like Gregor Blanco or even Juan Perez. The Brandon Crawfords of the world possess “survival tools” that allow them to provide value while struggling to get their offense developed to a satisfactory level. The Connor Cannons of the world don’t have that luxury — it’s Dingers or Bust. For the one tool player, the challenges are fierce, the margin for error thin. They walk a tightrope up the levels of development. The slightest degradation in their ability to get the tool to play in games — the balancing pole dips and the trapeze artist falls.

For Cannon, there’s one more element that makes the lesser-case scenario of the “Dingers or Bust” equation more likely. The man is a walking outpatient. The Cannon family buys surgical coupons in bulk so as to get the best price on surgeries to come. Before he was through as a Riverside Highlander, he’d already had surgery on both knees and suffered back and shoulder issues. Josh Norris told me this fall that he’d heard that Cannon had wrist surgery following Instrux. The curse of the Very Large Human™ most often comes in the form of the Very Large Body breaking down on itself.

And yet…and yet…and yet. The Universal DH is coming. The game is revolving around getting to power often enough, drawing walks, and damn the rest. The Giants preach hunting pitches for maximum damage. This is all Connor Cannon’s game. Stay healthy (enough to get on the field anyway). Defend the inner half. Hunt and launch. There’s a path to success for Cannon. Yes, it might be a Mark Trumbo level of success (the player whose amateur Southern California power exploits Cannon was most often compared to while at college). Or a Kevin Cron level of success. A lot of power, but not that much added utility outside of that. But that is a legitimate path with a fantastic outcome.

And it’s a path I, personally, would love to see the kid from Temecula climb. Because it’s been too long since we Giants fans had a Very Large Human™ to call our own.

If you liked this There R Giants post, why not subscribe?