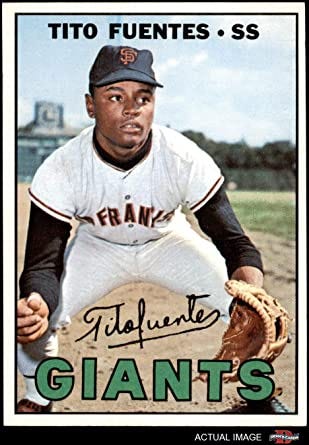

1967 Topps #177

After waxing poetic over the fierce beauty of Willie McCovey’s swing in our last installment, it might be something of a letdown to continue our journey to the keystone which, let’s be honest, has not been a hotbed of exciting prospect activity for this organization.

Nevertheless, today in our look back at the best minor league campaigns in Giants’ history we find stories of brash youth gone to seed and gone to glory and a classic baseball tale of a steady talent waiting for his opportunity.

Why Didn’t that Guy Make It?

Starting 2b — Platoon!

Jerry Lane, 1979 Fresno Giants (Cal League, A), 20 years old

.285/.360/.547, 100 Runs, 36 doubles, 29 HR, 88 RBI, 55 BB, 74 K

Mike Rex, 1978 Waterbury Giants (Eastern League, AA), 23 years old

.307/.397/.418, 20 doubles, 9 triples, 5 HR, 66 BB, 45 K

1982 Valley National Bank Phoenix Giants card

From a sheer “Best Seasons” perspective, Lane is the obvious call here, but I wanted to talk about Mike Rex a bit as well, so I’m going Lefty-Right platoon at this spot.

The Giants 10th round pick out of Santa Monica Community College, Jerry Lane was an instant success in pro ball. Literally! Though originally ticketed for the Giants Pioneer League team in Great Falls, Montana, Lane was sent to Fresno to open 1979 while waiting for the short season rookie league to begin. Lane never made it to the Pioneer League thanks to an historic opening salvo to his pro career. Over the season’s first month with Fresno, he crushed nine home runs, 14 doubles, and accumulated 92 total bases while hitting .388. It was enough to make him the California League’s Player of the Month — the first time that honor had gone to someone in his first month of organized ball in seven years.

That thunderous opening act earned Lane a feature article in the The Sporting News where his aggressive style of hitting was particularly noted. Jack Mull, the Fresno manager, gave a particularly effusive quote that would be grounds for a mocking in today’s game (and probably would lead pretty quickly to unemployment):

One thing he really shows is aggressiveness with the bat. And that’s most enjoyable for a manager. If there’s anything a manager hates, it’s to see a guy go up there and swing maybe only once every time up. Jerry doesn’t get cheated. He might take one pitch, but most of the time he’s swinging.

I suppose we know which side of the Belt Wars Mr. Mull would have been on.

The brash, good looking, Lane, who did side work as an extra in movies and also had a pilot’s license, had a strong sense of what he wanted to accomplish and how to accomplish it. He took an attack mentality to the plate (“I mean, I really want to hit it hard”) and sensed that bringing power from the middle of the diamond was a ticket to the majors.

“My goal is to hit .350 with 20-plus home runs. Second basemen are usually just infielders. But if I can hit .350 with power, it would be a quick way up there.”

Lane certainly accomplished his power goal in the ‘79 season anyway, clubbing 29 home runs and 68 XBH overall — both leading a team that had future All Star Chili Davis on it. He finished behind the Dodger’s Mike Marshall in the Cal League’s Rookie of the Year and MVP voting but was listed on the post-season All Star squad. The success would never be duplicated however. Lane would hit just 12 more home runs in his short career, including nine in 1980 with Shreveport. By 1981 he was in the Brewers’ system.

Possibly it was that ultra-aggressive approach ended up undermining his success. In that extraordinary first month of action, Lane struck out just seven times in 125 at bats. That rate would increase greatly over the rest of the year, finishing with 74 Ks in 492 ABs as the batting average dipped lower. Or perhaps it was just another in a long line of California League mirages. But for one glorious season, Jerry Lane was maybe the best minor league 2b the Giants ever had.

Mike Rex’ story is very different from Lane’s, though it ended similarly in bitter frustration. The Giants’ 18th round selection in 1976 out of tiny Linfield College, Rex was a classic ‘70s “contact and defense” type middle infielder, battling through at bats and making himself a tough out. He used those attributes to get as close to a big league career as possible before falling short. In Rex’ first full season, he played shortstop for Fresno across from a similar “contact and walk” guy, Joe Strain. And Rex’ Fresno season was even better than the Waterbury season I’ve listed above — he posted an .869 OPS, driven by an OBP over .400. He even stole 19 bases. His performance in 1978 might have been the more impressive however, given the tougher competition and much more difficult hitting conditions in the chilly Eastern League. He ended the year with a flourish, collecting seven hits in his final 10 at bats to meet his goal of hitting .300. And, following his second consecutive excellent season, the Giants rewarded him with a major league call up the final week of the season. Rex watched, but he never got in a game that week. And he began what turned out to be a bitter wait for another chance.

From a modern perspective, the thing that would pop out most about Rex’ stat lines was his incredible control of the strike zone. Over those two seasons, the right-handed hitter walked 143 times while piling up just 84 strike outs, all while hitting .310 — reminiscent of Bill Mueller’s climb through the system. But in 1979, Rex would fail miserably in the PCL, hitting just .233 and slugging just .298. His timing couldn’t have been worse. In the middle of that season the Giants moved 2b Bill Madlock to Pittsburgh for a trio of pitchers. With Rex scuffling it was his old double-play partner Joe Strain who got the call to audition for the role, not Rex.

Unimpressed by Strain’s time in the lineup, the Giants next turned their attention to the free agent market to fill the 2b position. In 1980 they made the unfathomable choice of signing the injured and poorly-performing Rennie Stennett. And then in 1981 they reversed course and signed an aging (but still good) Joe Morgan. All the while Rex waited in Phoenix — having gotten over his initial issues and gone right back to hitting .300, walking more than he struck out and playing great defense. In fact, Giants Manager Frank Robinson saw the latter for himself during the 1981 strike when he spent much of the summer watching the Phoenix team (a vigil that was greatly responsible for Bob Brenly finally getting called up). Robinson specifically called out Rex’ defensive work to The Sporting News, and with Joe Morgan dropping hints that he might retire after the season, it seemed like Rex’ time could be coming. But that winter Morgan decided he wasn’t quite through yet, and to make matters worse the Giants traded for Royals’ 2b prospect Brad Wellman who was installed in Phoenix lineup, pushing Rex to the AAA bench. His final year in pro ball, Rex played in just 61 games, and became so dispirited that manager Rocky Bridges began using him as a mop up pitcher just to get him into games (“It’s been a pretty tough year on him” Bridges said). And that was it. Constantly the second choice behind one player or another, Rex never did get that second call up, that chance to try his excellent eye (174 walks against 121 Ks in his minor league career) against big league pitchers. Never got the chance to show off his glove. Never got to measure himself against the best. For four seasons in Phoenix he waited for the call that would never come again.

Future Major Leaguer

Starting 2b

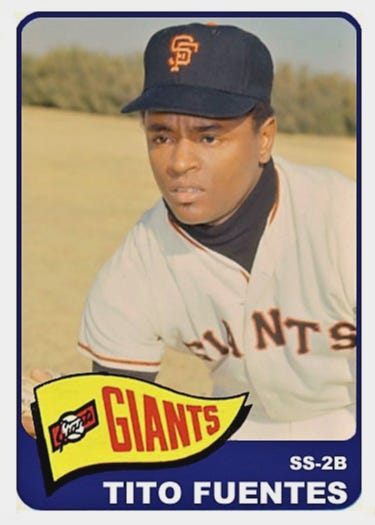

Tito Fuentes, 1965 Tacoma Giants (PCL, AAA), 21 years old

.302/.339/.543, 25 doubles, 5 triples, 20 HRs, 14 SB in 416 PA

1971 Topps Collection

Tito Fuentes career, on the other hand, was a testament to good timing. Signed by the Giants just after his 18th birthday in January of 1962, Fuentes was one of the very last players signed out of Cuba before the United States’ February 7, 1962 embargo went into effect, locking that island’s prodigious baseball talent out of the American game for generations.

The transition to a new country was bumpy for the teenager, as Fuentes hit just .220 in the Florida State League that first year. But by 1963 he was getting into the swing of things. Even the cold climes of the Midwest league didn’t dampen things as the 19 year old Cuban thrived, posting a .901 OPS in Decatur with 40 SB. That success earned Fuentes a late season promotion all the way up to AA. Notably, the switch-hitting Fuentes showed a pretty tight control of the strike zone that year, with 32 walks against just 45 strikeouts, helping him post a career best .409 OBP. That discipline began to slide in the following seasons, however, possibly as he began to sell out for more power.

The 1964 season would begin an uptick in Fuentes’ home run production that would last for three years, but it came at the expense of a huge increase in strikeouts. While hitting a career high 15 longballs between AA El Paso and AAA Tacoma that year, his strikeouts would balloon to an unwieldy 104 — by far the worst of his career — against just 33 BB. That trend would continue through his 1966 rookie year with the Giants, when he hit a career best 9 HRs in limited playing time, but did so at the expense of a crooked 57 K to 9 BB ratio. The following year that aggressive style would be exploited by major league pitchers as he slumped to a .209 batting average and was returned to the minors. By the time Fuentes came back to the Giants, he had also returned to heavily contact-oriented style of play, and he’d never again flirt with either double digit HR production, or elevated (for the era) strikeout rates.

But before he crashed and burned with his big swing in San Francisco, Fuentes had one extraordinary power year in AAA. Tacoma was by no means a friendly hitting environment — the cold, the rains, the heavy air, the wind, all made for a pitcher friendly environment in the far northwest. Of Fuentes’ teammates in 1965, only the supremely powerful Ollie Brown managed more than Tito’s 20 HRs. Brown, who was coming off a monster 40-homer season in Fresno the year before, paced the team with 27 longballs. The newly acquired Bob Burda, who had hit 45 HR in two seasons with the Pirates’ AAA team managed just 11. And Dick Dietz, who had a 35 homer year just two seasons earlier, barely broke into double digits with 10.

But somehow the diminutive Fuentes made the old Tacoma yard play small. He walloped 20 big flies that year, and 50 XBH in all, while playing in just 96 games. All told that .543 SLG that Tito produced in 1965 was not just the highest of his career, it was an amazing .185 points higher than any number he ever produced in the big leagues. It was also the 8th highest SLG in the PCL that year, despite playing in probably the least friendly hitting environment in the league. Other than Jerry Lane’s surprise season in the Cal League, it was the biggest power explosion that the Giants have every seen out of a 2b prospect, and gave a very uncharacteristic view of the player who would go on to hit just 45 HRs in 13 big league seasons.

We can only imagine, however — as no archival images or film exist — that Fuentes played that season with the elán and flourish that would definitely come to characterize him, and win the hearts of all of San Francisco. Fuentes was often referred to as a hot dog, but to my memory that term was never really used as a pejorative with Tito the way it so often was with others (I see you Willie Montañez and Derrel Thomas!). His outsized style of play spoke to pure joy and happiness, a genuine sense that he was playing the game, not working the game. It’s a shame that the internet — that source of so much human history — seems to have absolutely no images of Tito’s inimitable batting stance (from either side of the plate). The way he would corkscrew himself with the number on the back of his jersey facing the pitcher, flattening his bat over his shoulder, ready to uncurl. How he managed to have strikeout rates as low as he did (as low as 5-6% for several years) while using such busy and over complicated swing mechanics is a minor miracle.

There are a few shots on the Oakland Tribune photographer Ray Riesterer’s website that speak to Tito’s flair in the field, and a short audio track on You Tube of Chris Speier describing what it was like to play as Fuentes’ double-play partner. But for the most part the fun of watching Tito’s game seems to have vanished for those who weren’t around to see it in the first place. The headband over the hat, the crazy arm angles, the dancing leaps, it was all fun and fantastic and expressed a joie de vivre that is so often lacking from the big leagues. It’s no surprise at all that Fuentes would go on to make a name for himself in the broadcasting industry, becoming the Giants first ever Spanish language broadcaster, a position he holds (though with some interruption) to this day. Fuentes is the Forever Giant who somehow isn’t always remembered among the players who carry the Giants tradition forward from out of the past. But those who saw him will always remember.

There’s other thing that’s missing from archives that I would so love to see again. The most famous of his home runs — the one that put the Giants in the lead to stay in Game 1 of the 1971 playoff series against the Pirates. My family was sitting in the Right Field Upper Deck seats in Candlestick that day and so never did see the ball leave the yard. Cut off from the view below us, we could only judge the moment’s drama by watching Fuentes’ own reaction, leaping for joy as he ran the bases. Willie McCovey would blast a mammoth shot two batters later, obeying my Mother’s cry moments earlier to “hit one up here where we can see it, Willie!” But it was little Tito who had the big swing that day, coming up huge when it mattered most.

EDITOR’S NOTE: I realize that this list seems, so far, to be simply recounting members of the 1971 division-winning Giants’ lineup! And though that team does loom large in my childhood memories, I promise we’ll branch out from them in this series — and soon!

On this Day in History

The last lineup challenge was, of course, the 2014 Fresno Grizzlies, who rumbled to a 9-4 win in Las Vegas where they knocked a young Noah Syndergaard out of the game in the top of the 1st inning.

Brown, DH

Cavan, 2b

Peguero, CF

Dominguez, 3b

Parker, RF

Joseph, C

Anders, 1b

Jurica, SS

Fairley, LF

Reichard, SP

1974: Pete Falcone struck out 12 in a complete game victory over Salinas. That gave the hard-throwing Falcone 132 Ks in his first two months with Fresno. The left-hander had been the Giants 1st round pick the year before out of Kingsborough Community College in Brooklyn and his ascent would be rapid. After striking out 172 batters in 17 games in the Cal League, Falcone would finish out the year with 7 more dominant starts in AA Amarillo. In all he finished his only full season in the minors with a 2.95 ERA and 207 Ks. On Opening Day 1975, Falcone was in the Giants rotation. But after a promising, if bumpy, rookie campaign, the Giants shuttled him off to St. Louis in return for 3b Ken Reitz. Have you noticed in these old stories how messed up the concept of “development” was, especially for Pitchers?

2012: Pablo Sandoval declared himself ready to return to the majors with a two-homer day in Fresno. The Panda had been out since May 3 with a broken hamate bone in his left hand. Sandoval would return to the Giants lineup the next night, but typically the hamate injury would hamper his power stroke. He’d hit just three more home runs over the next 3.5 months. He broke his power drought with four homers in three days Sept. 19-21, setting the stage for his 6 HRs that post-season, culminating in a memorable performance in the World Series.

2019: Victor Bericoto drove in 7 runs in 20-11 romp for the DSL Giants. Bericoto’s big day included an RBI single, a two-run double, and his first professional HR — a Grand Slam. At the end of his first week as a pro, Bericoto had already eight hits in six games, including four XBH. Though he’d often be outshined by his spectacular teammate, Luis Matos, 17-year-old Bericoto would also receive a late-season promotion to Arizona after producing a .956 OPS in his debut in the Dominican.

As you probably saw, the A’s reversed course and offered to pay their minor leaguers when all 29 other teams committed to continuing the stipend. That John Fisher had to be, essentially, shamed into it and that his front-office employees are still struggling, has no doubt materially damaged the organization’s reputation going forward. But it’s still good to see. Now if we can only get to a point where these guys actually get to play some and continue their development!

Ah, Tito Fuentes! He was “my” second baseman. I thoroughly enjoyed his unorthodox batting stance, and his obvious love of the game. I had Hal Lanier’s baseball card as a younger kid, but Tito captured my imagination more.

Thanks for the stories about Mr. Lane and Mr. Rex - I had never heard of them. Although my impending marriage may have distracted me, but even so I had already moved out of state and I was still a couple of years away from discovering Baseball America. It was a veritable information wasteland in those days.