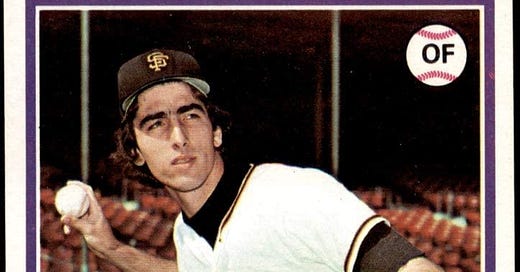

1978 Topps Edition #384

For those of you who have been with me since the beginning — and I’m sincerely grateful if you’ve been reading my stuff all along — you may recall that after the spring shutdown last year I started doing a series on the very greatest seasons by prospects in SF Giants history, position by position. In each case, I highlighted an all-time great prospect year for a player who would go on to have a successful big league career, and another who, for whatever reason, never quite made it at the top level. You can find them all here:

Greatest Seasons C

Greatest Seasons 1b

Greatest Seasons 2b

Greatest Seasons 3b

Greatest Seasons SS

Greatest Seasons RP

But then a funny thing happened: baseball suddenly started up again and there were new and interesting things to write about in the present day without having to reach back into the history books. And, because of that, the series remained oddly incomplete. I had reveled in the greatness of Willie McCovey and Jim Ray Hart, scraped around the rather uninspiring history of Giants middle infield prospects. I’d even tackled the greatest seasons by relief pitchers, primarily because I wanted to tell the extraordinary, and largely forgotten, story of Masanori Murakami’s American career — a career that broke cultural barriers and also engendered an international controversy.

But I never got around to tackling the two positions that really dominate the Giants’ history — outfield and starting pitchers. In large part, I was overwhelmed by how many choices there were in each case and couldn’t figure out how to whittle them down. However, in honor of yesterday’s podcast with Maria Guardado and our little game of “who was the greatest prospect?”, I think the time has come to finish the job. Why, after all, did I choose options such as Steve Ontiveros and Pete Falcone when asking Maria to identify the greatest Giants prospects? Well, friend, let me tell you a story…..

So, I’m going to wrap this all up with two omnibus editions, where I’ll count down the five greatest performances by the guys who “made it” and those who didn’t. Up first, it’s the position that was the glamour spot of the Giants organization for the first two decades of its existence: outfield.

Future Major Leaguers

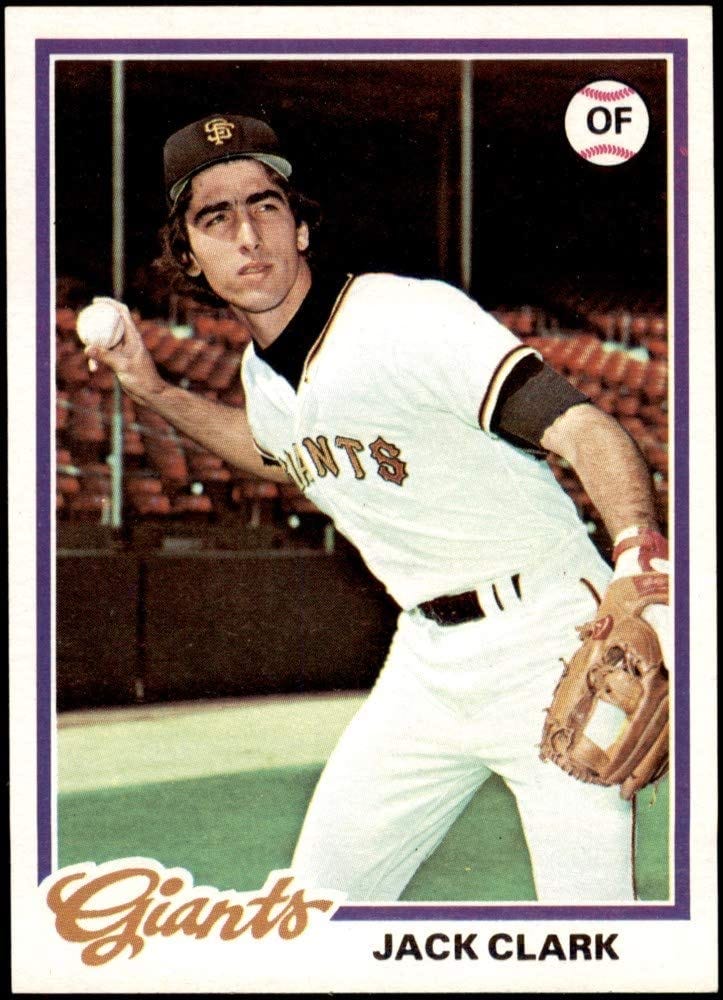

1982 Topps Series

It’s easy to look back in baseball history from our Moneyballed-up smarter-than-thou 21st century positions and think: “they didn’t know WHAT they were doing back then!” As with most self-congratulatory revisionist thinking, our vision of the past is much more likely to add distorted layers of falsity than it is to clear the way to understanding. But if we really wanted to find a player who was a victim of his era, Bakersfield’s own Steve Ontiveros isn’t a terrible guy to look at. Before anyone had ever thought about a “Greek God of Walks,” there was a teenaged Ontiveros, taking a cool 100 free passes, while showing off a sweet left-handed swing that would have made Will Clark proud. What the corner guy (he also played 3b and 1b) didn’t do much of was hit for power. His 18 HRs this year was the most he’d hit as a professional until a 20-bomb season in Japan when he was 32 years old. He’d reach double-digits just once in his 8-year major league career (10 with the Cubs in 1977). And for most of his career, the focus was firmly on what he couldn’t do rather than what he could. Today we’d say he didn’t profile very well. Back then they just didn’t know what to do with him. But Ontiveros managed to hit .274 while walking (309) more than he struck out (290) over 2,543 major league Plate Appearances. He might not have quite lived up to that youthful promise, but one wonders if things would have turned out a little better if the tenor of the times had been more attuned to things he could do well.

TIE: Jose Cardenal, 1961 El Paso Sun Kings (Sophomore League, D), 17 years old

.355/.467/.669, 39 doubles, 35 HR, 108 RBIs, 64 SB, 109 BB, 97 SO

Ollie Brown, 1964 Fresno Giants (California League, A), 20 years old

.329/.412/.671, 23 doubles, 11 triples, 40 HR, 133 RBI, 66 BB, 117 SO

The tales of the OF talent that the 1960s Giants couldn’t figure out what to do with are legion. Willie Kirkland, Leon “Baby Wags” Wagner, the Alou brothers, Jose Tartabull. They dropped quality major leaguers like loose change down the sofa year after year — and yet somehow managed to have the league’s worst LF/RF combination in 1966! Here are two more to add to the pile. It’s virtually impossible to know what to do with minor league statistics from the 1960s. There were dozens of leagues, a proliferation of levels —seriously what the heck is a D level Sophomore League? Levels of competition were scattershot to say the least. But, my god, just LOOK at those stat lines!

We’ve encountered the wild winds of El Paso before in this series, but there’s just no way to look at a 17-year-old producing 81 extra-base hits while stealing 64 bases in just 128 games without salivating. Ollie Brown hit 40 HRs as 20-year-old. FORTY! And while the careers of this pair might not have been sensational, they collectively played 31 seasons in the big leagues. What did the Giants get from them? Not a whole lot. Cardenal took 23 PA with the Giants before he was packaged off to the Angels for a young Jack Hiatt, who turned out to be a tremendous Farm Director over the decades but didn’t exactly become the team’s catcher of the future. Ollie Brown was selected in the Expansion Draft of 1969 and immediately became a 20-homer a year player for the Padres. Ah Horace Stoneham, you could have taught the Rockies a few things about mismanagement.

What were the Giants thinking? It’s frankly inconceivable. At the start of the 1981 season, the Giants made the inexplicable decision to keep 21-year-old Chili Davis on the Opening Day roster. Coming off back-to-back excellent years in A+ and AA, it was clear Davis was a rising star. But he’d never played a game in AAA and the Giants had no real spot to play him with an OF composed of Jack Clark, Billy North, and Larry Herndon. And so, for nearly two months at the beginning of that year, the supremely talented youngster sat tattooed to the bench. He rarely played (8 games) and almost never started (just twice!) while luminaries such as Jerry Martin, 1b Dave Bregman, and even old PH Jim Wohlford had regular turns in the spot-start rotation. It made no sense.

Finally, just before Memorial Day weekend, the Giants woke up as from a dream and realized: “hey this kid should probably be getting some at bats in AAA!” Released from purgatory, Chili went off! He averaged an extra-base hit every other game in Phoenix, finishing with a scintillating .605 SLG and 1.036 OPS. Ultimately, he produced career highs across his slash lines — doubtless, in no small part due to the offensive environments of the PCL. But it wasn’t an illusion, Davis would go on to be one of the better hitters of his generation and a darn good hitting coach when he was done. In 1984, he’d post a 148 wRC+ — or nearly 50% better than league average — and 19-year career average was 121. Dude could hit! Don’t sleep on those 40 SB he accumulated in those 88 games either. Once upon a time, speed was a big part of Chili’s game. But after coming a HR shy of a 20/20 year in his rookie season of 1982, he decided jogging around the bases was more his preferred speed, and never again stole more than 16 in a year.

Speaking of speed, here it is: the platonic ideal of a ballplayer from my youth. I mean, really, Mays is. But I got the 30-something version of Mays mostly as a child and while his instincts running the bases were still incredible to behold, the days of leading the league in SB were long gone when I came on the scene. Bonds, however, I saw from the start. The power/speed combo in its absolutely perfect form.

And here it was, in 1965, immediately on display in the youngster’s very first professional season in Lexington, KY (which probably wasn’t much fun for a young black man in 1965 America). He hit for power. He dazzled on the bases. He struck out a lot. He was Bobby Bonds. As much as he ran, he always had strong success rates. In this first year he was thrown out just 5 times. Over his big league career, he’d maintain a success rate of 74% while swiping 461 bags. The .300 batting average wouldn’t be part of his typical years going forward, as his extreme aggressiveness tended to bring the averages down and send the strikeout rates up. But his ability to impact the ball — and the game — was unimpaired by all those whiffs. And if there were a metric for determining how entertaining a player was, Bonds’ numbers would certainly have been off the charts. While it’s inarguable that modern analytics have given teams greater insights into how to win baseball games, it’s to my mind equally clear that a tremendous amount of the beauty and splendor and spectacle of the game has been lost to time as well, first with the stolen base artist, now with the starting pitcher. The game could really use a dash of Bobby these days.

To be honest, this is really a misnomer. Jack Clark wasn’t an OF for the Lafayette Drillers. He was their 3b, as he had been the year before in Fresno. Between those two seasons he’s officially credited with an almost unbelievable 109 errors and his days as a 3b were soon over. But putting him in the OF where he belongs allows us to focus on what Jack Clark really could do — the man purely raked a baseball. For those of us who remember him, the violent slashing of his bat is easy to picture in the mind. The home runs that seemed to tear a whole in the atmosphere they passed through. And yet, despite wielding what can only really be described as “vicious” swing — there’s a reason he was known as “Jack the Ripper” — Clark was, to our modern eyes, a contact specialist. Look at those numbers again. That’s a 19-year-old in AA striking out just 11% of the time while tying for the lead league (with teammate Gary Alexander) in HRs.

And, unlike Cardenal above, this particular part of Texas wasn’t doing hitters any favors. The heavy, humid air in Lafayette seemed to suck the life right out balls. Besides Clark and Alexander, only one other Driller managed even double-digit home runs (1b Craig Barnes hit 12). The team as a whole slugged just .390. But there never was an atmospheric condition that was going to take the air out of a ball once Clark hit it.

Despite being a rather unheralded 13th round draft pick out of a Covina, CA high school, Clark demanded the attention of Giants’ officials. At the end of this, just his second full season, Clark would get his first taste of the big leagues — a 19-year-old clankmitted 3b who blistered minor league pitching over two and a half minor league seasons (his career OPS at that point was over .900). He wouldn’t stick right away. In 1976 he’d have yet another brilliant year in Phoenix before his second and final call up. But Clark would ultimately slash his way to the big leagues with the same brutal efficiency he showed to major league pitches. He ripped his way to the top!

Why Didn’t These Guys Make It?

2002 Topps “Signature Moves” series, autographed rookie card

TIE: Jessie Reid, 1980 Great Falls Giants (Pioneer League, Rk), 18 years old

.366/.457/.551, 16 doubles, 6 triples 5 HR, 14 SB, 38 BB, 24 SO, 59 Games

Bernie Williams, 1967 Medford Giants (Northwest League, A-), 18 years old

.271/.436/.502, 11 doubles, 14 HR, 55 RBI, 13 SB, 71 BB, 83 SO, 82 Games

Sadly, 18-year-olds showing power/speed tools in their debuts don’t always lead to such happy results. Jessie Reid is, arguably, the most high-profile development failure in Giants’ history. The 7th overall pick of the 1980 draft (just two years after another failed 7th overall pick in Catcher Bob Cummings), Reid started out strong with this sensational debut. He hit everything thrown at him, striking out less than 10% of the time, and showed a balanced attack. He finished fourth in the league in OBP and sixth in SLG, and the players ahead of him in both categories were all several years older. It was a glorious beginning. After that? He more or less just stopped hitting. In Fresno the average dropped to .246; in Shreveport .260. By the time he got to AAA Phoenix he was just a .231 hitter. And, while he never struck out a ton, he never made particularly impactful contact. In Phoenix he’d post a woeful .298 Slugging Percentage. The force of his draft pedigree would get him 8 games in the majors, but his career went on a steady downward trajectory after rookie ball.

A decade earlier, Bernie Williams went through much the same career arc. A gifted CF on a championship Oakland High School team, Williams looked like he might be yet another prodigious CF prospect. After a slow start in pro ball, a visit from his family coincided with a torrid hot streak which saw him bash 7 homers and knock in 21 runs over a six-game stretch. He ended the year 5th in Slugging and SB — ironically a future Giant finished just in front of him in both categories, Dodgers draftee Von Joshua — and third in OPS. But as with Reid, the short-season rookie ball was the highlight of his career and the numbers all dropped from there — except the strikeouts, which most definitely went up. Still his obvious physical tools pushed him to the big leagues and, in a short 1970 debut he actually went 5 for 16 with two doubles. Short auditions in both 1971 and 1972 saw him hit below the Mendoza Line, however, and his career was finished after 102 games.

Yep, I’m just a sucker for these guys! Show me a CF with homers and stolen bases a plenty and I will Charlie Brown that football till the end of time. I KNOW this is the time it’s going to work! Powell was actually a two-time 1st round draft pick, being selected by the Blue Jays out of Long Beach High School in 1991 before the Giants made him the 22nd pick of the 1994 draft. And like Reid and Williams above, his short-season debut in the Northwest League was a glorious triumph (.309/.389/.503). The strikeouts were a red-flag and they would almost certainly be his undoing as he advanced (in his first full year he struck out 131 times in San Jose) but the rest of his game promised big league success. He glided fluidly around CF gobbling up everything in the air, he raced around the bases, and he could put some juice into the ball. As was true with Clark in Lafayette, Shreveport was not an enviable place to hit for power. Teammate Armando Rios would manage just 12 HRs that same season. Powell’s 20/40 campaign surely marked him as the future CF in San Francisco. Alas, no. He struck out 243 times over the next two seasons in AAA and his star dimmed. Though he ended up having a .327 career batting average with the Giants, his big league career would be just 85 PA in 70 games.

EME, as he was affectionately known to fans, almost made the Michael Tucker gambit work. The Giants intentionally rid themselves of their 1st round draft pick in 2004 in a fit of destructive creativity, as a way to carve out the money with which to sign FA Tucker. Giants fans — and baseball fans, in general — viewed this outside the box solution with a collective moan. This, they said, is why there’s a box!

But then something amazing happened! When at last their first pick of the 2004 draft came, the Giants found to their delight that a player considered to be one of the most advanced hitters in a pretty light college class was sitting there waiting for them — Florida State’s Martinez-Esteve. EME was just a good old-fashioned masher, and one that the Giants’ current front office would surely appreciate. He was known for his patience at the plate, rarely swung at balls outside the zone and rarely missed those he swung at. He didn’t have huge power, but line drives flew off of his bat with regularity. By the end of 2005, Giants fans weren’t missing that 1st round pick all that much because here was a walking, bashing offensive star right out of the newly minted pages of Moneyball. Here was a star! But EME just couldn’t keep himself away from the surgeons. He ended each of his first three professional seasons in surgery, twice for injuries to his shoulders. And ultimately those shoulder woes zapped some of the zip from his swing. He was already a shadow of himself when he got to AA Richmond and things just never got any better. He was still playing Indy Ball through much of the past decade, but the days when his bat was a lethal weapon were long gone. Damn injuries.

And damn shoulder injuries especially! In 2006, during a promising age-18 season in Salem-Keizer, Thomas Neal dove back into 1b on a pickoff throw and popped his shoulder out of the socket. He’d ultimately need a surgery that cost him almost all of the 2007 season. But the following year in Augusta, he seemed as good as new, and over the next two years his star rose high enough to land him on the Top 100 prospects lists. Following a strong .803 OPS in hard-to-hit Lake Olmstead Park in Augusta, the now 21-year-old Neal exploded in the Cal League. He posted the 4th best OPS, the 6th best SLG, and the 2nd best OBP in the league, despite playing in the league’s most pitcher-friendly park. He also finished 3rd in total bases, collecting 67 extra-base hits overall. It was a thrilling performance. But the old shoulder issues started bothering him again the following year during a still-solid AA performance. They would never go away and despite a few “cups of coffee” with Cleveland, the Yankees, and the Cubs, his professional career was over at the age of 27 when it just wasn’t worthwhile fighting the pain and discomfort anymore. The ending of his Giants’ career was ignominious, traded to Cleveland for the dreadful final months of Orlando Cabrera’s career (poor O-Cab, who was a genuinely terrific player, did not leave behind a pleasant legacy in San Francisco). The weeding-out process is excruciating. It should have gone better for Thomas. It really should have.

Speaking of which, Todd Linden surely should have been the Giants first homegrown All Star OF since Chili Davis. What other result could have been waiting for him? The Giants were so certain that their powerful, switch-hitting 1st round pick out of LSU was a star talent that they sent him directly to AA to make his professional debut. Do you know how insane that is!?! Nobody sends players straight to AA! And he was good there! Right off, he mashed with a .314/.419/482 debut. AA? No problem!

In retrospect, there were red flags. Baseball America’s pre-draft scouting report noted that his “all or nothing” approach for power had allowed pitchers to exploit him successfully, and he tumbled from an expected top 10 position to the sandwich round. While hitting for admirable power in the Texas League, he also struck out 101 times in 111 games. Probably it was never much more complicated than that. He generated huge power from both sides by selling out and leaving himself vulnerable to the wily wares of advanced pitchers.

But still, let us take a moment to admire the beauty of that 2005 season in the Pacific Coast League. He’d already had two short appearances in San Francisco at the conclusions of the 2003 and 2004 seasons, and experience with big league pitchers certainly tend to raise batters’ stat lines when they return to AAA. Still, this was a mauling of epic proportions. Thirty home runs in 95 games! He finished one off the league lead in home runs despite barely staying past the All Star Game. His 1.120 OPS sits confidently amidst a flock of league-leaders from the Mountain Zone launching pads of Albuquerque and Tucson. His .682 Slugging was the best in the league — better than the guys who spent 80 games in the high air. It was astonishing. The Giants didn’t wait for an end of the year callup this time. This was showtime! After 95 games of treating AAA pitchers like his own personal chew-toy, they brought him up and installed him the lineup. And then….he didn’t hit. Not a lick. Over 60 games he produced a .216 batting average, four home runs and a strikeout rate that scraped 30%. Things were a tiny bit better in 2006 — at least he walked enough to have a respectable OBP — but 2 HRs and a 109 wRC+ doesn’t exactly cut it for a “bat-first” LF. The Giants moved on. There was a quick stop in Florida and then…that was it. The chances were come and gone and the next player was up. It’s just a brutal way to make a living, man. Pity all who chase the dream!

Some Moves

Giants DFA Luis Alexander Basabe

Giants trade RHP Shaun Anderson to Twins for OF LaMonte Wade, Jr.

As expected, Luis Alexander Basabe’s time was bound to come to an end this winter. Though the OF showed intriguing skills that the Giants surely would like to see more of, his lack of a remaining option was a ticking time-bomb for his place on the roster. Needing to make room on the 40-man to announce the Tommy La Stella signing, Basabe drew the short straw.

In response — and to address the continuing need for another left-handed bat in the OF — the Giants then traded RHP Shaun Anderson to Minnesota for a player who has much of the same skillset as Basabe, plus one extra option year! At 27, Wade is old for a prospect, and his lack of power limits his ceiling to an extra OF. But he’s athletic, has excellent speed, and, you guessed it, controls the strike zone well! In part-time action with the Twins the last two years, Wade has a nearly 1:1 ratio of walks to strikeouts, and an excellent 13% walk rate. A rangy OF, he might be a little stretched playing CF every day, but he certainly has the speed and glove to backup all three spots capably. Unlike the switch-hitting Basabe, Wade is a left-handed hitter only.

In the “life comes at you fast” category, Anderson was the club’s top pitching prospect just two years ago. But he struggled in his opportunity to join the starting rotation in 2019, as opponents found him easy to hit. Moved to the bullpen in 2020, he saw a tremendous rise in velocity and pure stuff, but he couldn’t figure out where it was headed most of the time, leading to a long stint in Sacramento. With the moves sending away Anderson and Sam Coonrod, the Giants are seemingly showing little tolerance for high stuff/low command type pitchers. Instead, it seems they’ve identified a very different prototype to pursue, as good friend GPT has identified:

I’ll be back with more under the radar prospects next week — if you have specific guys you’d like me to write about, don’t forget to drop suggestions in the comments. I’ve already got some great ideas from you! So, thanks! And, as always, thanks for reading!

And don’t forget to share or, if you’re able, subscribe! I’d greatly appreciate your support.

I stumbled on to this by accident and I am glad I did!

As a native of Danville, Virginia, I am partial to Leon Wagner's 51-homer season in 1956 with the Danville Little Giants of the Carolina League. :)

https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=945f2011

Ah, good old Downtown Ollie Brown! Misty water-colored memories...

As for disappointing OFers, I was thinking of Steve Hosey and Calvin Murray (who remains the fastest ball player I’ve ever seen play in person).

And then there’s the litany of Adam Hyzdu, Dan McKinley, Alan Cockrell, Ted Wood, Beni Simonton, et al. Sigh.